Pre-first world war: In Kovno Gubbernia, Russian Empire.

Presently: In Kaunas District, Lithuania

|

#kovno-1: The first conference of Hebrew (observant) academics in Lithuania (academics from Latvia and Estonia also took part) .It was held in Kaunas (Kovno) in |

#kovno-2: The first conference of Hebrew kindergarten teachers in Lithuania, held in Kaunas (Kovno) in 1930. |

#kovno-3: The second conference of Hebrew teachers in Lithuania, held in Kaunas (Kovno), 1921. |

|

#kovno-4: The Alter (or "Sabba")

of Slabodka Yeshiva, Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel |

#kovno-5: The heads of the Hebrew bank in Kovno. |

#kovno-6: Rabbi Isaak Elchanan

Spektor

|

|

#kovno-7: The heads of the Hebrew small businesses organization,Kovno 1933 |

#kovno-8:

|

#kovno-9: Heads of Jewish banks in Lithuania. |

|

#kovno-10: conference of rabbis in Lithuania, held in Kaunas (Kovno) in 1926. |

#kovno-11: Heads of the Jewish community meet Zalman Shazar ( the third President of Israel) in the Kovno train station in 1933. |

#kovno-12: Max Soloveichik (a Jewish minster member of the Lithuanian parliament), during a speech |

|

#kovno-13:

|

#kovno-14:

|

#kovno-15:

|

|

#kovno-16:

|

#kovno-17:

|

#kovno-18:

|

|

#kovno-19:

|

#kovno-20:

|

#kovno-21:

|

|

#kovno-22:

|

#kovno-23: Birthday

Party for Raya Popel Children at a birthday party in Kaunas, Lithuania

for Raya Popel who turned 2 years old. |

#kovno-24:

|

|

#kovno-25:

|

#kovno-26:

|

#kovno-27:

|

|

#kovno-28: Chanuka |

#kovno-29: Talmud Tora |

#kovno-30: Children in Hospital |

#kovno-31: |

#kovno-32: |

#kovno-33: |

#kovno-34: Kovno Yiddish Kindergarten, 1937 Picture given by Anat Rosen |

#kovno-35: Kovno 1936 |

#kovno-36: Kovno 1936 |

#kovno-36: My mother: Dina nee Levinshtain was born in Kaunas in 1914 Here she is with other members of her HaShomer Hatzair unit c1929 in Kovno.Avi Lishower |

#kovno-35: Dina nee Levinshtain with other member of Hashomer Hatzair in Kovno c 1929 picture given by Avi Lishower. |

#kovno-36:Hachalutz Hatzair in Kovno; Elchanan Fig (at the top), Sara Shner - Neshamit (second row from the top, on the right), Rivka Szunikanski (second row from the top, on the left), Ester Ritov (bottom row, on the right), Mordechai Szarszeniwski (bottom row, center), and Chaya Peltz (bottom row, on the left). Photographed in 1934. |

#kovno-37: A group of public figures from Kaunas (Kovno) together with some of the members of the Central Committee of the HaChaluts Zionist movement there, who were about to sail off to Palestine. In the photo: David Cohen (seated, second from the left), Israel Marminski - Marom, Moshe Cohen, Menachem - Mendel Roizenbojm. Photographed 1924 |

#kovno-38:Members of the Central Committee of the He - Chaluts Zionist movement in Kaunas (Kovno) in 1922. In the photo: David Cohen (in the center), Israel Davidson and his brother |

#kovno-39: |

#kovno-40: |

#kovno-41: |

#kovno-42: |

#kovno-43: |

#kovno-44: |

#kovno-45: |

#kovno-46: Raya and Eliezer Shiniuk (Siniuk) with their children. The parents and two of their children perished in the Kovno ghetto. courtesy of: Raya Gonen, grand-daughter of Raya and Eliezer Shiniuk (Siniuk) |

#kovno-47:Yerschmiel Siniuk, Kovno Ghetto 1943. He lost his arm while sabotaging amunition being sent to Germany. courtesy of: Raya Gonen, his daughter |

#kovno-48: Jakov was born in the Kovno Ghetto to Sonia and Meir Goldsmidt. In 1944 after the children acktion Sonia took Jakov out of the ghetto to hide in a monastery. She was killed by the Germans when she returned after refusing to say where Jakov was hidden. His father Meir survived and was reunited with his son after the war ended. The picture was taken in 1945. courtesy of: Raya Gonen, their cousin |

#kovno-49: Sanhedria orphanage in late 1947. |

#kovno-50: Kriger family with some of their Levine relatives, at home in Kovno Circa 1930 |

#kovno-51: Aronas [Aron] Moisey (Moshe) born in Kovno |

#kovno-52: Salmat Ber Itsik , son of Girsh , was born in Jurbarkas |

#kovno-53: |

#kovno-54: The Hebrew scouts (associated with Hashomer Htzair) - graduating |

| #kovno-55: A photo taken shortly before the immigration of my grandparents YOAV LAVIE |

#kovno-56: The last conference of Hebrew teachers in Lithuania, held in Kaunas (Kovno) in 1940. pictured: Leipziger, Panevezys, Scher Chaviva, Shilanski J. |

#kovno-57: Jewish children in the Kaunas (Kovno) ghetto looking at a sign forbidding Jews access to the river |

#kovno-58: Memorial at the Ninth fort |

#kovno-59: A group of female gymnasts, Jewish students in Kaunas in the 1920s |

#kovno-60: |

#kovno-61: Education staff and children in a Jewish orphanage |

#kovno-62: From left to right, Sara, Yitzhak, and Beyla Peshkin. It must have |

#kovno-63: Jewish Jewish fighters from Kovno |

#kovno-64: Jews from Kaunas (Kovno) who took part in a conference in 1930. |

#kovno-65: Children playing in a public park in Kaunas |

#kovno-66: At the park, 1922 |

| #kovno-67: Abraham Mapu (1808, Slobodka, Kaunas – 1867, Königsberg, Prussia) was a Lithuanian-born Hebrew novelist of the Haskalah ("enlightenment") movement. His novels later served as a basis for the Zionist movement. |

#kovno-68: Interior of Slobodka synagogue at end of June, 1941- it was vandalized |

#kovno-69: The staff of the internal medicine department of the Jewish hospital in Kaunas (Kovno) |

| #kovno-70: Patients and members of the medical staff of a Jewish hospital in Kaunas |

#kovno-71: |

#kovno-72: Kovno First soccer team at the Jewish athletic club in 1925 |

| #kovno-73: Jewish Ort school in Kaunas |

#kovno-74: Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Spektor 1817-1896 |

#kovno-75: |

#kovno-76: |

#kovno-77: Mirjam Naftalovitch with son and mother, Kaunas 1937 |

#kovno-78: Naftalovich Hirsh 1933-1941 |

#kovno-79: |

#kovno-80: Taibel, Romm, Naftalovitz and Kulman Family from Kovno Names of People in Photo to the right submitted by; Reuven Taibel of Bat Yam. |

#kovno-81: Names of People in the photo to the left |

#kovno-82: Postcard sent by Hirsh- .Hirsh - Yoseph Taibel - a soldier in the Russian army Submitted by grandson Reuven Taibel |

#kovno-83: Postcard sent by Hirsh- Yoseph Taibel from Minsk in March 1916 his wife Tsipa-Chava in Kovno Submitted by grandson Reuven Taibel |

#kovno-84: Children of Taibel family from Kovno - refugees in the first world war in South Russia ~ 1916. From left to right: Libbe-Esther, Leib (Arie), Mere (Mirjam), Don (Daniel),and Ida Submitted by Leib's son - Reuven Taibel |

#kovno-85: |

#kovno-86: |

#kovno-87: |

#kovno-88: |

#kovno-89: Purim in Kovno, 1936 |

#kovno-90: Kowno, Lithuania, Dina, Avraham and Zelda Garnun, before the war. |

#kovno-91: Kaunas, Lithuania, The second convention of "Hamoreh" the Hebrew |

#kovno-92: From right to left; |

#kovno-93: Jonas and Antonina B. Paulavicius and their children Kestutis and |

#kovno-94: Members of the Jewish council in the Kovno ghetto, among them is Top row: from right, Rabbi Abba Sneig, M.Kopelman, Rabbi Shmukler, Dr. |

#kovno-95: July 27, 1941 |

#kovno-96: October 1943 |

#kovno-97: From left: Natan Shulman (survived, later became a rabbi in Israel) Zepta-Shabtai Freidman |

#kovno-98: Benjamin Kaner, Sabsie Kaner, Jacob Jake Kaner, Sholom Solomon |

#kovno-99: Esther Blumenthal nee Sandler was born in Kaunas, Lithuania in 1909 to |

#kovno-100: |

#kovno-101: |

#kovno-102: |

#kovno-103: Exterior of the Rabbi Yits?ak El?anan Spektor orphanage, Kaunas, Lithuania, 1927. Photograph by Gorshayn. (YIVO) |

#kovno-104: Members of Gordonia saying farewell to a comrade, Jakov Miler, at the railroad station, upon his departure to Palestine, Kaunas, 1938. As the Hebrew inscription notes, the photograph was taken “on the seventh day of Adar, on Thursday morning, 9:40 am.” Photograph by Judelio Milero. (The Ghetto Fighters’ Museum/Israel) |

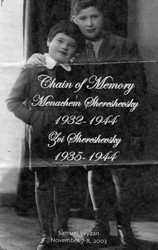

#kovno-105: Menachem and Zvi Shereshevsky perished in the holocaust |

#kovno-106: Shoshana Strasburg 1919- 1945 perished in the holocaust. |

#kovno-107: Pinchas Sheinson was the first husband of Pnina Tory. Father of Shulamit. He perished in Kovno during the holocaust. |

#kovno-108: Rami Neudorfer wrote on facebook; In the photo: the actors Diana Blumenfeld and Moshe Kopritz in a scene from the play "Matura" (Kaunas 1936) Of blessed memory Otto Kraendl. I did not find any details about the fate of his widow Lyuba, who survived the Holocaust and immigrated to Israel. |

#kovno-109: Kovno family picture from 1932 |

#kovno-110: Toba-Feiga Teomim Israel on the left. She passed away in Kvno in 1941 as the Nazis took control. |

#kovno-111: July 31. 1944.. The day Kovno was liberated from the Nazis. |

#kovno-112: On the left |

#kovno-113: Isaak Elkhonon Virovich with wife Chana and daughter Miriam. The family peished in the holocaust in Kovno. |

#kovno-114: Gita Yodidio Daughter of Mischa Yodidio and Alena HenaLina Yodidio |

#kovno-115: Sheine Malka Virovich (Gutman) with her daughter in law and her granddaughter |

#kovno-116: Malka daughter of Berel Leib Kalish and Gutman (Tuvia) Virovich pose with their granddaughter Alice, while waiting for her parents to join them for Shabbat. Photograph | Photograph Number: 97644 |

#kovno-117: Cilia Cicilia Meirovitz Birth:1901 |

Please share your comments or photos or links for posting on our Guestbook Page here: egl.comments@gmail.com

Dov Lipec

From “Yahadut Lita” (The Jews of Lithuania), p. 273

Kovno is located on the bank of the Nemun River in an elongated valley traversing from South to North. The Nemun and the Vilya rivers neighbor it. On the Vilya bank, across from Kovno, the Vilijampolis suburb known as Slobodka is located. On the other side of the Nemun river, atop rolling green hills lies the suburb Elkost (during the rule of the Russian Empire, this area belonged to Suvalk, while the rule of Napoleon governed the Polish area at that time).

The town of Kovno was established in the year 1030 by the Lithuanian prince Koinas. Jaroslav, a Russian prince, ultimately defeated Koinas, however. Koinas originally established a fortress and palace on a peninsula in the area where the river Vilya joins the Nemun, in the west. This eventually became Kovno. From 1031 until 1280, no written records regarding Kovno exist. For the duration of the wars between the Lithuanians and Germans – wars that lasted from 1280 to 1420 – Kovno was a battlefield, and, according to extant records, the town was demolished and rebuilt fourteen consecutive times. Only in the year 1410, after the prince of Lithuania Vytovet (Vytautas) defeated the Germans near the villages Grunwald and Tannenberg in Prussia, did the building of the town started progressing independently.

In 1795, during the third division of Poland, the Kovno area was annexed to the Russian Empire. During World War I, in 1915, the town was conquered by Germany, although it was soon liberated from the German occupants and became part of Poland. Kovno became the temporary capital of Lithuania in the years 1919-1939.

The Origin of the Jewish Community

Already at the beginning of the fifteenth century, during the days of Prince Vytovet (Vytautas), Jews started arriving from Ukraine and Poland to settle in Kovno. Coming first to Vilna, they then moved on to Kovno. Original historical documents – the Lithuanian metrikai, the statute, and the books of the state of Lithuania - all record that the first Jews to arrive in Lithuania settled in Trakai, Grodno, and Brisk, among others, and came to Kovno as merchants, settling there temporarily. Soon, however, a few Jewish families settled there permanently. German merchants who came from the Union of Hanza towns had a monopoly on commerce in Kovno from before the rule of Prince Vytovet, and they now fought the Jews viciously, forbidding them to settle in the town. In those days, Kovno contained huge warehouses, owned by residents of the Hanza, and the owners had close business ties with Gdansk and Konigsburg.

It is reasonable to suppose that the first Jews to arrive in Kovno came from Trakai, as Trakai is located on the main road from Vilna to Kovno. Other than these, Jews from Keidan (Kedainiai) also arrived in Kovno, and it appears that it was the latter who established the Jewish settlement in Vilijampole, or Slobodka. Kovno’s original Jewish inhabitants, however, came from Trakai. The Trakai Jews were renowned for their business skills and ambitious nature. Some of them were in contact with well-known princes and thus received leases granting them taxation rights.

It is difficult to say with certainty who the first Jewish settler in Kovno was, but according to the Lithuanian metrikai, it was Daniel, originating from Trakai. He leased the taxation station in Kovno between 1450 and 1470 and was considered extremely wealthy man by local standards. His son Zev, known in the metrikai as Zov, inherited his holdings. Daniel’s house in town was estimated to be worth around two hundred shek of coins, an amount equal to 250 dollars, that was considered exorbitant amount Daniel also had other possessions and holdings outside of town. Amongst these was a hill later known as at that time.

Mount Napoleon; historians investigating Kovno’s history say that this hill was previously known as Jewish Mount (Zydu Kalnas). In fact, Kaunas' Jewish Mount was renamed after Napoleon to commemorate the illustrious French commander, as it marked an important success in his campaign against Russia. It is believed that from the top of this hill Napoleon stood proudly watching his army cross the Nemum, which at the time delineated the border between Poland and Russia. This was his army's first steps into Russia. (http://www.inyourpocket.com/lithuania/kaunas/en/feature?id=55514)

At the time the hill was still called Jewish Mount, the Kings of Poland-Lithuania forbade Jews to settle en masse in Kovno. They permitted certain Jews with special rights, like Daniel from Trakai and his sons, to settle there as leasers of property from the King. Such Jews brought with them servants, agents, clerks, and other Jews who were registered as their assistants. We can see evidence of the prominence of the Jewish merchant Zajev, for instance, by looking at the special permit that King Kasimir obtained for him. This concession was obtained in spite of the Teutonic Order, which prevented Jews from travelling in Prussia at the time. King Kasimir obtained special permission for Zajev to visit Gdansk and other areas of Prussia for business reasons.

Vilijampole did not belong to Kovno at that time. It had its own jurisdiction and the land belonged to the Radziwil family, the princes of Keidan. Jews had an easier time obtaining permits to live there. The Vilijampole Jewish community was greatly enlarged by inhabitants coming from Keidan. It became a satellite of the Keidan community and during the days of the Committee of the Jews of Lithuania, Vilijampole belonged to the Keidan district in regards to taxation.

The Jews of Kovno were periodically exiled by the town’s leaders and were forced on many occasions to leave Kovno. Their good fortune was that they did not need to go far; they were allowed to settle in the nearby Vilijampole. Usually, they would stay there for some time before returning slowly to Kovno, only to start the cycle again. During almost every new ruler, they were once again expelled from Kovno.

In 1464, a plague swept through Vilna and Grodno and many Jews came to settle in Vilijampole. The first Polish king to forbid the settlement of Jews in Kovno was Jegaila Kasimir. This sanction was not diligently observed, and many Jews succeeded in living in Kovno despite it. In 1492, Alexander the First again ordered the expulsion of Jews from Kovno. In 1495, an expulsion of all the Jews of Lithuania took place –Jews of Kovno and Vilijampole, as well those from all other settlements of Lithuania, were sent away, and Lithuania was rid of its Jewish inhabitants. We must note here that at this time the governor of the region was a man of Jewish decent by the name of Avraham Josefovic, a Christian convert. He subsequently became the minister of the Lithuanian treasury. Even during the expulsion of Jews, he remained the governor of the town, controlling the taxation, which had earlier been under the control of Zejev. Avraham Josefovic diligently tried to help the Jews of Lithuania, and after a while they were allowed to return to their homes.

In 1503, Alexander the First received a large amount of money and revoked the expulsion of the Jews, allowing them to return and returning some of their possessions. The residents of Vilijampole returned to the area immediately. The Jewish Kovno residents had a more difficult time returning as the Christian residents of Kovno, who had special Magdeburg privileges, prevented the Jews from entering. When Sigmund took control of the kingdom, however, this situation changed. Old Sigmund liked the Jews, and encouraged industry and commerce among them. During his rule, Jews came to the town without trouble or restriction. Christian merchants now wanted Jews in town, for the Jews assisted them in controlling the revenue and taxation that was sent to Prussia.

Documents from 1528 record the minister of taxation as being a Jewish man named Aaron Humovic, who was responsible for collecting taxes on salt and wax. Nevertheless, it appears that the town rulers were very stubborn and the Jews were once again made to reside in nearby Vilijampole. Even Sigmund August, a reformer who was known for his tolerance of the Jews, continued to forbid them to settle in the main area of town.

The Committee of Jewish Autonomy in the area of Lithuania-Poland soon split. In Lithuania, its former members established the Committee of the State of Lithuania during the days of the rule of Sigmund August. According to the orders of the king, 1551 saw the establishment of provincial committees in Lithuania, governed by rabbis. According to Lithuanian State records, the Jews of Kovno belonged to the Grodno district and the Jews of Vilijampole to the Keidan district.

At the time, old Kovno was situated in a part of town later known as Altstadt. It is possible that not even the whole of Altstadt was populated at this point. During the days of Sigmund August, special privileges were granted to professional Jews, allowing them to settle in Kovno. In documents of the day, one such professional Jewish pharmacist, named David, is mentioned. A legal document from October 1559 tells of in a trial involving Moshe Mahonovic Malakovic (Metrikiai Lithuanian Sodyvenik Dial number 39, pal. 246). There is also mention of a Jewish doctor by the name of Doctor Todras living in Kovno.

The Seim of 1547 petitioned the King to establish in Kovno (as well as Brisk, Grisa, and Salat) large warehouses to store wood, simplifying the exportation process and government taxation procedures. The King granted the suggestion, and records of it can be found in Kaniga Pasalaskaya Metriki Litvaskovi. In 1558, a Jew by the name of David Shmerelovic, from Brisk, received a special permit to collect taxes of salt and wax for a period of three years. In return, he was to pay the King’s treasury an amount of 4000 coins. Record of this permit can be found in Aktavaja Kaniga Metriki Litvoskovi Zapysi number 37, pal. 161.

On February 8, 1580, King Stefan Baturi established an order called Akti Zefadavai Rasai # 3221. This order came about as a result of a complaint filed by Trakai Jews on June 19, 1579 regarding the merchants of Kovno, who did not allow them to enter the town for commerce, in spite of their legally granted commission pursue commercial ventures in Lithuania. The king decreed that the merchants of Kovno could not prevent any other merchants from entering the town. He also promised to investigate the complaint further as soon as the war that he was engaged in ended. This can be found in Akti Gradavo Vilna-Kovna-Trakai #3175.

On March 23, 1589, Aaron Schlomowitz, the head of the Trakai Jewish community, asked in the name of his community that King Sigmund the Third intervene on the behalf of the Jews. Kovno merchants had once again forbidden any merchants from Trakai to come to Kovno and, furthermore, took control of their merchandise, in spite of commerce permits given to the Jews by the king of Poland and the prince of Lithuania.

The Establishment of an Organized Jewish Community in Kovno

At this point, the Jewish community of Kovno was small. It did not have its own rabbi or synagogue, although a few synagogues and established communities could be found in nearby Vilijampole. As the Jewish community in Kovno became larger, the government tried to make rules against it. Jews were forbidden to come to the market during market days and were made to live in a closed ghetto on Janowa Street. In the year 1601, the King instituted severe rules against the Jews of Kovno. During the wars between Poland and Russia, and later on, during the war with Sweden, the town passed from one ruler to another and the Jews suffered greatly. After a betrayal of Christian merchants, King Jancavsky, in 1682, ordered the expulsion of Jews from Kovno. Those Jews who were already deeply rooted in the town were forced to move to Slobodka. After a long and tiresome negotiation, the rulers permitted Jews to return on the condition that they would give 1/15th of all their income to the rulers.

Upon the return, the Jewish community of Kovno became more organized. In documents from the beginning of the 18th century, there is mention of the first rabbi of Kovno – Rabbi Azriel. It could be that during those days there was a religious Beit-Midrash, a religious school, in town, and Rabbi Azriel was only a judge to the Jewish people of the town. The head of this judicial outpost lived in Vilijampole.

The 18th century brought with it many disasters. A war between Poland and Sweden took place. In 1781, a huge fire destroyed almost the entire town, and then, during the Seven Years War, Kovno was conquered by the Russian Empire. Yet tther disasters took place. Even in this difficult time, the Christians did not overcome their hatred of the Jews, instead preventing more Jews from entering the area. They were especially upset by the fact that some Jews bought land from the people whose homes had been burned during the fire. This land was outside of the ghetto area of Janowa Street. When the Christians learned that the Jews had lost papers indicating their special permission to settle in town in the fire, they demanded that Jews be expelled according to the old rule of the Kingdom of Poland, which had forbidden Jewish settlement in the town.

In 1753, the authorities expelled the Jews of Kovno, taking their homes, gardens, and property. Some of the Jews left to go to Vilijampole, while others settled in areas outside of the mayor’s monopoly. From there, the Jews would come to market days in Kovno. This greatly upset the governor of the town – Pruzer – and in 1761, pogroms took place against the Jews, and Jewish homes were burned. All the remaining Jews were expelled to Vilijampole. Prozer tried to expel the Jews from Vilijampole as well but did not succeed.

In those days, the family of Soloviachik became well-known throughout Kovno. Family members included Rabbi Mosche, the rabbi of Vilijmpole, and his brother Abraham. After the pogrom and expulsion of 1761, these two brothers started legal procedure against the town mayor or governor. This trial took place in Warsaw and lasted until 1782. The Jews were helped and supported by the Radziwil family of Keidan.

In 1782, the trial ended with the verdict that the Kovno municipality must pay fifty thousand Zloty to those Jews who had been molested or somehow harmed during that period, as well as covering the expenses of the trial. The town mayor, Prozer, received two weeks’ jail sentence. The Jews returned to the town, and retrieved their possessions. To commemorate their victory, Reb Schmuel the Small from Vilna wrote the Scroll of Kovno. It became custom to read this scroll in the Kovno synagogue every Purim. From that year, the Jewish community in Kovno flourished. Amongst the people who returned to Kovno was the well-known business man Aba Solovecik. Still, there were attempts by Christian merchants to forbid the Jews to settle, although they were not successful. The heads of the Jewish community made sure that Jews would not loan money to gentiles against homes that they owned outside of the Jewish area. They did so wanting to prevent any complaints stating that the Jews were trying to obtain land outside of the permitted area of residence.

The Jews of Kovno Under Russian Rule

In 1795, Lithuania was annexed by Russia, and Kovno became a regional central town in the Vilna Gubernija in 1796. It was also a border town, as the suburb Elkost belonged to Prussia. In 1808, the town Elkost was annexed by Napoleon to the Warsaw Princedom that split from Prussia. However, the anti-Semitism did not quell in Kovno during Russian rule. In 1797, the Christian residents complained to Czar Paul the First, asking him on their behalf to expel the Jews according to the old rules that were still written in the books, and to take their possessions away. The Czar began an investigation. The leaders of the Jewish community did not sit idly, proving instead that the Christian complaint was unfounded and, as instructed by the minister of the region Rafnin, the Czar ordered to let the Jews stay in town and continue with their business without any molestation. He recognized that the Jews were numerous in the city’s population, and their part is taxation was significant, and this blind hatred toward them could lead to a destruction of the town from a financial point of view. The Jews decided to use these special priviledges that they received from Russian authorities to settle outside of the ghetto. Many of the town clerks did not understand the new rules and they kept asking for bribes from the Jews. In addition, new rules were implemented making it difficult for Jews to receive real estate from gentiles who owed them money. There were occasions where the authority had to intervene when Christians did not repay debts to the gentiles. The news laws hoped to prevent this.

At this time, the Jewish community contained 1508 souls. They had a syngaogue – a beit midrash known as the Old Beit-midrash – although they could not support it for an extended period of time, requiring the services of the Jewish community in Vilijampole. Jews wanting to settle in the town of Kovno had to pay a certain amount of money to the Jewish community in Vilijampole for the permission to leave.

In 1812, Napoleon conquered the area. On June 2nd, his large army crossed the Nemun river from the side of Elkost. The Jews found themselves between the battling armies and suffered greatly during this war. When the Russians returned to town, a big celebration occurred. There was a celebration in the central town square, and during the reception some of the Jewish representatives greeted the Russians with Torah books, bread, and salt.

During the days of Czar Nikolai the First, the Jews received more restrictions. This occurred according to the request of fourteen Christian citizens of Kovno. The Jews were only allowed to build in certain suburbs like Slobodka on Janova Street and between Karmelita and Rumsiskes. They were not allowed to fix their wooden homes and were ordered to replace them with homes built of stone. In 1846, they were only allowed to sell their wooden homes to people who vowed to replace them with houses made of bricks. The public servant Reb Tsvi Hirschl Navizar worked tirelessly to change the new rules. These were difficult years for the Jews since new rules forced Jewish families to give a certain amount of young boys for long army service. A practice of kidnapping poor Jewish boys to fulfil the draft began.

After the failed Polish rebellion in 1831, the Russian administration improved its treatment of the Jewish residents in Lithuania. Nothing was changed in the books, but they allowed the Jews to settle in all parts of the city and, with the help of the Jewish public servant, in 1839, they were allowed to take part in the elections of town government. Still, they limited the Jews’ capability of buying real estate in certain areas of the town. In 1842, Kovno became the capital of the region and split from Vilna. This occurred in spite of the fact that the town was fairly small and not sufficiently developed. On one occasion, the Russian czar crossed Kovno and was shocked to find it in such neglected condition. The explanation offered for this neglect by the governor of the region was that the cause of this was the limitation of the rights of the Jews to buy real estate. The Czar wanted to receive detailed information about the issue and in 1846, he received detailed documents, which contained an appendix asking him to cancel all the restrictions imposed upon the Jews. This was signed by forty two gentile owners of estates, merchants, clerks, and important residents. Upon reading the recommendation of the minister of the region and the general governor, the Czar cancelled in 1858 all the limitations placed upon the Jews of Vilna. In reality, all of these limitations were cancelled in 1864. From that point on, quick progress of modernization of Kovno began, and the Jewish population became more prominent.

In those days, the Jewish minister Moshe Monitfiori came from the West to visit Kovno with his wife and other Jews. He was a guest in the home of Simon Markel, visiting also Vilijampole, where he met the minister of the region and conversed with him in regards to the condition of Jews in the region. To learn more about the effect of the canceling the restrictions on the Jews, we can learn from these statistics: in 1847, there were 4986 Jews in Kovno and Slobodka. Slobodka contained 2973 of them. In the year 1864, the Jewish community in the two towns had risen to 16,640. In 1897, it contained 24,448 souls, which was about 36% of the population. It only took about fifteen to sixteen years before Kovno became an immigration destination for Jews from small villages and towns.

The Jewish Community and its Institutions

In 1862, the Jewish community in Kovno purchased a large piece of land situated on a rolling green hill to house the Jewish cemetery. Until then, Kovno Jews buried their dead in the cemetery in Vilijampole. As there were days when the rivers would overflow and Kovno would be flooded, rendering Vilijampole unaccessible, the Jews had often had to ignore certain religious rules and bury the deceased days after their death. A new Kovno cemetery prevented this inconvenient situation. During that same year, the community established a burial society in Kovno, called Chevre Kadishe.

By 1864, there were already 19 synagogues in Kovno other than the old Beit-midrash. Soon, the synagogues started funding Jewish charity organizations. In 1876, Zusman Navichovic and Tsvi Rabinovic established a society named Mahzikhei Ytzkhaim that founded a school for Torah studies. There were between three and four hundred students at the school, and six or seven teachers who taught religious studies, Hebrew, Russian, and math. The annual cost of the school was 1600 Rubles and it was paid for by community taxes on kosher meat and by donations from Chevre Kadishe, the burial society, which gave 15% of its profits to the school. There was another school of Torah studies in the old Flan, and was connected to the synagogue Nachlat Israel.

In 1854, Rabbi Hirschl Navizar established without much difficulty a brick hospital in the town. In 1875, this hospital was run by Tankhiel Levinson and Zejev Funkin in a very modern fashion; its annual allocation was 15,000 rubles. The hospital was constructed to hold four hundred patients, and yearly, 4000 patients were taken care of in it. In 1862, Tsvi Shefir and Rabbi Ytzhak Jazef Solovechik, the father of the reknowned rabbi Yosef Dov Solovechik of Brisk, established a society in support to the fallen, by the name of “Somchai Noflin”. By the end of the century, a Jewish home for the elderly had been established, as well as an orphanage.

The renowned rabbi Ytzhak Elhanan Spektor was received as the rabbi of Kovno in 1864 and led the community until 1896. During this period he succeeded in elevating the community of Kovno to a prominent position in the Jewish world. In his day, the town became a center for social and political work of rabbis of the Russian Empire. Spektor was born in 1817 in the town of Rus, in the region of Grodno. He married when he was thirteen and settled for six years in Volkovysk. After serving in Bazlin, Graze, Nasovic, and Novgorodok, he received the rabbinical chair in Kovno, where he remained for thirty-two years. During this time, he established the Kovno yeshiva. He became very prominent in the Jewish community, settling many political-religious Jewish issues that were debated in the community. He died in 1896, whereupon his sons took the name of Rabinovich. Spektor was a central figure in the greater Jewish community and was known throughout the Russian Empire. In 1875, he forbade the use of the Etrog from Corfu, the most northerly of the Ionian Islands. He decided against the use of "etrogim" (lemons) from Corfu as a result of the pogroms that the Jews had suffered in that area [editor’s note: there were anti-Semitic demonstrations only in 1891 at Corfu, not in 1875 as implied here. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia of 1906, “in 1875 he decided against the use of ‘etrogim’ (citrons) from Corfu, because of the exorbitant price to which they had risen.” E. G. L.] During Spektor’s lifetime, there was no significant Jewish action or mission that he did not take part in. For these reasons, Russian authorities treated him with much respect.

Spektor had many assistants and helpers. At the head of one committee he established was Reb Jacov Livschitz, who became known for his fight against the Enlightenment Movement, and, later on, against the Zionists, who saw the solution to the Jewish problem in a more secular light than he preferred. This political institute that Livschitz stood at the head of was later known by many as the ‘black party’, nicknamed thus by the writers of the Enlightenment Movement. Rabbi Spektor himself was not as fundamentalist or extreme in his views, and kept in touch with the Enlightened of the town, who, like others, treated him with great respect.

At that time, the educated and enlightened of the town established their own synagogue, Ohel Jacov. This synagogue was first opened in the school on Mapu Street, and later received a special building on Ozvishako Street. The synagogue’s Rabbi Ytzhak Elhanan was opposed to the Musar movement, and fought silently against its leader, Israel Slanter. Rabbi Israel Slanter soon left Kovno for Slobodka, where he established, together with Netta Tsvi Finkhel, known as the Saba/Grandpa from Slobodka, a yeshiva that was later named after him – Kneset Israel. This yeshiva was supported by the financier and donor Lachman, from Berlin. Ten years later, after a long struggle, a second yeshiva was established in Slobodka by the name of Kneset Bet Ytzhak, named for Ytzhak Elhanan Spektor. This yeshiva was established in hopes of weakening the influence of the Musar movement that had become very prominent in the town. The founder of the yeshiva was Baruch Bar Leibowtiz; at that time he also established a kolel, a school for torah studies. These schools drew many students from near and far, and for this reason, Kovno became a central location for Jewish spiritual life – one of the biggest such centers in Russia at the time.

During the 1880’s, Rabbi Spektor headed a large foundation established for the residents of the region of Vilna who suffered starvation and, later on, used some of the foundation money to help Jews who had suffered in pogroms in Russia. Of the same generation as Spektor was the famous Jewish doctor and public worker Dr. Ytzhak Feinberg.

From the 19th to 20th Century

The second half of the 19th century stood almost in its entirety as a period of large financial improvement for the Jewish community. In the 1850s, a large road was built between St. Petersburg and Warsaw, crossing Kovno. During the Crimean war of 1855, the Western Alliance put a blockade on all the waterfronts to prevent enemy crossing. Thus, at the time, the only commercial contact with the west passed through Kovno via the new road. In 1863, a railroad was established from Kovno to the border with Germany. At that time, the large fortress in Kovno began to built, an undertaking that was not to be finished until the beginning of World War I. Thus, Kovno became a fertile land for energetic merchants, real estate salesmen, and Jewish bankers.

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, Kovno had an established middle class. The Jewish population increased in size, and spread to new parts of the town, like falan, sanci, karmelita, and others. In Kovno, Slobodka, and the green hill of the cemetery, a new class of working Jews, laborers, owners of small workshops, clerks, movers, and vendors was established. In the year 1887, Jewish craftsmen in the Kovno district numbered 5479. For them worked 1143 assistants and 776 apprentices. Amongst them were 445 tailors and seamstresses, 380 cobblers, 336 cigarette makers, 300 butchers and fishermen, 445 bakers, 338 gardeners, 509 owners of carriages, and 595 other laborers. These included bookbinders, smiths, barbers, millers, oven-makers, and others (1889). The social and financial distinction between the Jewish classes reflected on the cultural and political life of the community. The middle class was the most influential in community, spawning the intelligentsia of the Jewish society that included physicians, lawyers, engineers, writers, and teachers. Most of the political representatives of the community were part of this middle class. Amongst them were Reb Isabel Wolf, Doctor Ytzhak Feinberg, Moshe Bramson, Leon Oszinski, Abe Solovechik, Simon Markel, Jehezkel Jakel, Rabinovitsch, Mordechai Rabinovitsch, Tankhiel Levison, rabbi Nisan Kirk, Zajev Frunkin, Bahalach, and Altman.

Eventually, some members of this social class became aware of socialism, and went on to become founders of the Bund movement in Lithuania. The end of the 19th century saw emergence of such writers as Shmuel Rosenfeld, Shmuel Leib Gordon (1867-1933), Gordon’s brother-in-law Avraham Bel Avigdo (originally Shelkovic, uncle of Nachum Goldman, 1866-1921). The new generation received a traditional education, most of them studying in cheders and yeshivas. The Talmud-Torah was founded in hopes of providing a secular education for young people from poor backgrounds. At the public Jewish school, which was under the management of Rodman, as well as at the private Jewish school, hundreds of Jewish youth studied. Fifty or sixty Jewish students studied among three hundred fifty-nine students in the public Russian gymnasium. At the gymanisum for girls, thirty or forty girls were Jewish among three hundred and ten students.

The Beginning of the Twentieth Century

Before the start of World War I, in 1914, the number of Jews in Kovno reached 40,000 out of a general population 87,986 (almost fifty percent). In the year 1908, about 92% of all the Jews in town were considered town residents (miestieciai). Of 145 merchant guild members most were Jewish. That year, the town gave out 1,439 commercial licenses. The main branches of commerce were export of wood products, cloth, agriculture, eggs, chickens, and livestock. Import took second place, but was limited by the low standards of the general population. That same year, 164 licenses for manufacturing were given out. In the 64 industries in town worked 2443 laborers. The production that year was valued at 5,178,575 Rubles. There were only four large manufacturers and they employed 1740 laborers. These were under the ownership of Christians, mostly Germans. Most of the businesses owned by Jews, with the exception of the flourmills, were small industriers and the work conditions were difficult. Very few Jewish laborers were hired to work in the factories owned by Christian people. A number of Jews worked on ferries on the Nemun and Vilya rivers. Eventually this difficult work and the meager compensation caused many Jews to immigrate, mostly to the US and South Africa. In the year 1908, 600 Jews left the country. Most were laborers, craftsmen, and clerks. The number of people who needed public aid reached 4000 that year.

Of 21 lawyers in Kovno that year, 4 were Jews. Of 23 lawyers’ assistants, 12 were Jews. Of 24 doctors, 15 were Jews. In 1911, there were twenty-five synagogues and houses of prayer in Kovno. Most belonged to professional unions, such as the butchers, tailors, etc. One belonged to Hasidic Jews. The youth studied in dozens of cheders in town, the most famous being the cheders of Adamovisch, Kalinitski, and Sokstalitski. There were two yeshivas in Slobodka as well as the old beit-midrash, and a synagogue belonging to the tailors by the name of Etz-Chaim and the Chloiz Naviezer.

In the public Jewish school, 250 students studied. In the public secular schools studied 148 Jewish boys and 154 Jewish girls. In the 7 private Jewish schools studied 213 boys and 152 girls. 158 children attended the Talmud-Torah school. Altogether studied 1462 Jewish students – a quarter of all the Jewish school-aged children. Next to the public Jewish school, a professional school for carpentry and metalworking was established in 1882. A professional school for girls was also opened. At the Paltov gymnasium for boys, 166 Jews studied out of 502 students. At the Maria gymnasium for girls, out of 468 girls, 228 were Jewish. At the teacher’s seminary, out of 243 students, 126 were Jewish. Dozens of Jewish girls attended the gymnasium of Ignativo.

A very important foundation for the community institutions was the Korovka, or the taxation system. In the year 1907, it brought in 33000 Rubles. That year, the Jewish community divided this income the following way: 11,800 Rubles to the Jewish hospital, 3300 Rubles to the old home, 2000 Rubles for Talmud-Torah, 4800 Rubles to the various schools, 1200 Rubles to hire additional teachers for Jewish religious studies in the Russian Gymnasium, 1000 Rules to feed the poor, and 6000 Rubles for the synagogue, 900 Rubles to the rabbi, 600 Rubles for managed of metrikai books, 7000 Rubles for the rabbinical house in town, and 6000 Rubles for the municipality in order to run the taxation system itself.

Already by 1905, Julius Blumenthal edited the Kruvinski Telegraph. After a while the name of the paper was changed to Severo Zafadni Telegraf. It was a Jewish newspaper in the Russian language that fought against bad treatment and prejudice under the Czarist rule; this newspaper was used as a bridge between the Jewish population and the young Lithuanian intelligentsia. These contacts helped to establish a political compromise between the Jews and Lithuanians in the election of the Duma. When the Russian revolution failed in 1905, many members of the Jewish community were arrested and sent to the Siberian gulags. Some were able to escape to America, where they continued their socialist activities.

Already in the election of the first Duma, the Jewish public servants preferred to make agreements with the Lithuanians rather than the Polish landowners, and Kovna was used as a central location for this policy. To this end, the lawyers Ozer Finkelstein and Petras Leonas established a committee. Amongst the Jewish members were Doctor Feinberg, A.B. Wolf, Finkelstein, Tsvi Wolf (born in 1869 in Kovno, studied law in Moscow, was the head of the central Jewish bank in Kovno, was in the Judenrat in the ghetto, were he preished in 1942), Doctor Wirsblovski, Jud Bacharah, L and M Solovecik. The Lithuanians were represented by the engineer Petras Vileisis and others. Vileisis went on to become the town mayor. [Petras Vileisis January 25, 1851 - August 12, 1926. He funded the publication of the prohibited Lithuanian press, and organized its distribution. In 1875-1876 he published illegally the manuscript newspaper Kalvis melagis (Blacksmith the Liar) in Lithuanian. In 1877-1878 he published several Lithuanian books in St. Petersburg. In 1904 he founded a printing-house and a book-shop of Lithuanian books in Vilnius. He petitioned the officers of Russian authorities demanding the lift of the ban on the use of Latin alphabet in printing Lithuanian books. In 1904-1907 Petras Vileisis was the publisher and official editor of the first legal Lithuanian daily newspaper Vilniaus Zinios (The News of Vilnius).] His brother Jonas Vileisis and others were part of the committee as well.

Due to cooperation within the committee, a Jewish man by the man of Leon Bramsen was chosen as the first Duma. Leon Bromsen, son of Moshe, was born in Kovno in 1869 and studied law in Moscow. He died in Marseilles in 1941. He was the brother-in-law of Ozer Finkelstein. Since Leon signed the Weiburg declaration, however, he could not be elected to Duma the second time. Thus, the lawyer Shakhna Avramson was elected. He was born in 1861 in Kovno and studied law in Moscow, fighting for human rights. He was elected as second Duma in 1907 and joined the left wing of the party of KD. In the third and fourth dumas, the jury of Lithuania was represented by Naftali Friedman from Paneveziai. Friedman was born in 1863 and studied law in St. Petersburg. While in the Duma, he joined the KD party and took part in different committees regarding education and religion. He died in 1921 in Kisingen. Originally, the Jews of Kovno wanted Oscar Gruzenberg to be elected, but the authorities denied his rights to candidacy. In May 22-29 of 1909, there was a meeting of Jewish public workers in Kovno; people came from all over the Russian Empire. This meeting was called Discussions of Jewish Public Workers from the Pale of Settlement. During those times of the reactionary Czarist government in Russia, the meeting of such a committee made the Jewish communities of the Empire very excited. The license for this committee was given to A.B. Wolf. During the conference, forty-six Jewish communities were represented by 120 delegates. Amongst the members were: the head rabbi of Moscow, rabbi Maze, the famous lawyers Shliosberg, Weinbar, doctor Isidor Elyeshiv Friedman, who was known as Shavot, and other renowned public workers. Secretaries included Tsvi and Hans Wolf as well as Julius Blumenthal. The committee elected twenty-one people, amongst them nine from St. Petersburg. The decisions that this group made primarily concerned the struggle for equal rights for Jews of the Russian Empire, organization in the Jewish community, and attaining Jewish national and cultural autonomy. They also researched the financial and social situation of the Jews of Russia and developed propaganda with the aim of increasing professional productivity and modernization of Jewish charitable and social institutions.

In 1908, the local Zionists of Kovno, amongst them Doctor D.M. Schwartz, Doctor A. Lapin, and Doctor A. Bloscher, established a library named after the famous Hebrew writer Avraham Mapu of Kovno. This library fulfilled a great need in Kovno. The members of the Bund had founded a library earlier but after the failed revolution of 1905 were forced to dismantle it. The library named for Mapu was also meant to be used by the yeshiva students of Slobodka. Originally, the heads of the yeshiva forbade the young men to use the secular library and instead sent special ‘spies’ to prevent any yeshiva students from going to the library. In spite of the sanction and the punishment that yeshiva students received if found in the library, many visited it anyway. Its educational and political influence on the youth of the town greatly increased, and many young people became Zionists. Soon thereafter, another library was established by the Jews of the Enlightenment movement. There was yet another library in Slobodka, and Aba Bloscher owned a huge private library.

There were also several active societies in Kovno, among them a Society for Lovers of Hebrew, the archaic language. A branch of the Jews who spread enlightenment founded a musical and drama club for Jews. Underground Zionist unions and youth movements also existed.

The First World War, the Expulsion of the Jews, and German Occupation

The first to suffer in result of the war among the Lithuanian Jews were the Jews of Kovno. Soon after the outbreak of war on the first of August 1914, thousands of residents left the town. As the warfront approached, a few thousand Jews transferred to Vilna and other settlements in the area. On May 18, 1915, the head of the Russian army, the great prince Nikolai Nikolaiovich ordered that all the Jews, without exception, be expelled from the city of Kovno, and practically from the entire region. This order was immediately executed with no pity or consideration toward even those who were sick or handicapped. On the eve of the Jewish holiday Shavuot of 1915, the town was cleared of Jews. Jewish apartments and businesses were officially shut down by the police and military authorities, although in reality Christians took over the Jews’ possessions and looted their homes. Only a minor part of the exiled Jews were able to find shelter in Vilna; most were taken south and east, deep into Russia, to areas far from the border.

Only a few months passed before the German army took over the Russian front and conquered the regions of Kovno, Vilna, and Grodno. Germans invaded Kovno on August 18 of 1915 and Vilna was taken a short time later, during Yom Kippur, September 1915. The few Kovno Jews who had stayed in Vilna now immediately returned to their homes in Kovno, but found their possessions looted and homes destroyed. In addition, their synagogues and public institutions were robbed. The Koral synagogue suffered less destruction than most. The books of the Mapu library were hidden in this synagogue and most of them survived. Eventually, about 9000 Jews returned to Kovno; 20000 Jews of Kovno were spread all over the Russian empire. The Germans established their own municipality in town, and a representative of the Jewish population by the name of Shabtai Shuval became a member of this organization. Shuval was also, at that point, the leader of the Jewish community.

Rabbi Avraham Dubar Shapir, son of Salman Sender Kahana was born in Kobrin and was the grandson and the great-grandson of the rabbi Chaim of Volozhin. He was born in 1871 and died in 1943. In 1913 he was the head rabbi of Kovno. He died in the ghetto during World War II, and was the head rabbi of Kovno for thirty years. During World War I, however, he was absent, and was replaced instead by Rabbi Israel Nisan Prak, born in 1867 in Karmain and died in Tel Aviv in 1938. He was a Kovno rabbi for around forty years. Other than him, there served also a military rabbi, doctor Rosenhak, as well as Levi from Leipzig. They came with the German occupants from Germany; others who came included Jewish writer Arnold Zweig, the artist Herman Schtruk, and the author Sammy Gruneman, as well as Doctor Leo Deutschlander. All of them became very active in the life of the small Jewish community. They initiated the establishment of a Jewish high school that was taught in the German language, whose headmaster was Doctor Josef Talibach, followed by the rabbi of Altuna-Hamburg. Later, in independent Lithuania, this high school went on to become the Hebrew Real Gymnasium. The Jewish activists also took care of the Jewish POWs who lived under very difficult conditions. In general, residents of Kovno did not suffer from starvation and epidemics as much as the residents of Jewish Vilna. For some reason, the German occupation in Kovno was, relatively speaking, much easier on the population than the occupation in other places.

The two yeshivas of Slobodka had been transferred, during the years of the Jewish expulsion, deep into Russia. The yeshiva Kneset Beit-Ytzhak stayed after the war in Kaminic-Litvosk (now in Belarus) and never returned to Lithuania. The yeshiva Kneset-Israel was reopened during the German occupation, as early as the fall of 1915, with the assistance of the Germans themselves. Headed by Rabbi Baruch Levi Horowitz and Rabbi Nisan Javlonski, eventually this Slobodka yeshiva regained the original headmaster, Rabbi Finkel, known as the Grandpa. It had completely returned by 1920, establishing itself in its original location.

During Independent Lithuania

After the signing of the peace treaty between Russia and Germany in Bresk-Litvak, the Jews started returning to Kovno from deep Russia, but the return of the war refugees and exiles lasted a long time and some did not return until the end of 1923. Even then, thousands of Jews stayed in exile in Russia.

Kovno’s name was now changed to Kaunas. In 1919, the town became the capital of Lithuania. Many Jews from the nearby shtetls settled here, and the town became the center of commerce and administration in Lithuania. As the new Lithuanian country was established, the Jews started developing a national cultural autonomy, starting in Vilna. The Jews organized their communal spiritual life using democratic principles. The main influences on the life of the community were the Zionist parties who controlled Jewish Street and left their imprints on various social aspects of the community, especially that of education.

From the end of 1919 until the middle of 1924, a ministry for Jewish interests was established in Lithuania. In addition, a Jewish National Rat was founded. Kovno became popular for meetings of Jewish committees; in 1920 and 1923 there were meetings of the national Jewish organization. Such political involvement flourished in the Jewish community of the 20s, and those years saw a struggle among the different Jewish political parties and cultural entities, especially in regards to issues of education.

The head of the Jewish community of Kovno was Doctor Meshulam Wolf. Born in 1877 in Kovno, he studied in the Russian Gymnasium and later in the University of St. Petersburg and the Berlin University. He was one of the first prominent Zionists of Lithuania. For some time he lived in Tel Aviv, serving as a judge in the 1930’s. Shortly before World War II, he returned to Lithuania, where he was sent by the Soviets as an exile to Russia and died in a Siberian camp in 1942. When the Congress of the Jewish committee was cancelled in Kovno, new societies for assistance – one named Zra and one Adat Israel – were established to take care of the Jewish community, although they never had the same influence and control of the community as the Jewish committee had once had.

Jews in the Municipality of Kovno

During the reign of the Czar, Jews had no rights to either elect or be members of the municipalities. Only in towns that had a large Jewish population did the Czarist rulers appoint a few Jews to the town municipality. However, the number of such Jews could never exceed 10% of the members of the municipality. Even then, this 10% had very limited rights in votes and could not take part in important decision-making committees. This situation also existed in Kovno, despite the fact that the Jews made up a large part of the population and much of the ecomical welfare was contingent upon the Jews’ input, as commerce, crafts, and significant parts of the industry were in Jewish hands.

During World War I, invading Germans took complete control of the town. In 1918, there were changes on the warfront, and the Germans started preparing to split from Kovno. Some of the local businessmen, especially the Jews among them, like Doctor Max Solovecik, Doctor Mischulam Wolf, and Leib Garfunkel, decided to take control of the municipality when the Germans were aboutto retreat, and thus to avert chaos in the period when the town was without rule. Max Solovecik was the son of Avraham Ada, and was born in Kovno in 1883. He studied history and Eastern languages in St. Petersburg and later in Germany and edited the Yverska Zydn and Rosazweiz, newspapers that were established by Russian Zionists. When Lithuania became independent he became a minister for Jewish interests and was elected as a member of the Seim. He later moved to Berlin and in 1933, emigrated to Israel. He died in Jerusalem in 1957. Leib Garfunkel was the son of Tsvi Hirsch, born in Kovno in 1896. After attending the Russian Gymnasium, he studied law in St. Petersburg and Kovno. He was one of the heads of the Jewish community in Lithuania, and was the head secretary and later the vice-president of the committee of the Jews of Lithuania. He was a member of the Kovno majorija committee and was a member of the Lithuanian Seim. He established a daily newspaper Yiddishe Schmidte and was its first editor, as well as founding other newspapers. He was also a representative in the Zionist congress. In 1940, he was imprisoned by the Soviets and sent to jail until the Nazis invaded Lithuania. He was later among Judenrat members in the ghetto of Kovno, and in 1944 was taken to Dachau. He survived, and, after the war, he moved to Italy where he headed an organization for Jewish refugees. In 1948 he immigrated to Israel and wrote The Destruction of Jewish Kovno.

The Lithuanian, Jewish, and Polish activists were all able to work together beautifully in establishing a temporary municipality that slowly took control of all the municipal interest and elementary needs of the townspeople. When the town was conquered by the Polish, they were pleasantly surprised to find a very efficient political committee already in place. This rule was based on coalition of the three national branches in Kovno – the Lithuanians, Polish, and Jews – and the principle that heads of the committee changed in a rotational order.

In 1924, there were democratic elections of the municipality, and the Jewish population was represented in this election in all the different branches and classes, as the town mayor was the engineer P. Valeisis and his assistant was Y. Raginski. Dr. Meshulam Wolf was the head of the town committee at this point. The Jews were represented in all the various prominent municipal committees, and a large number of Jewish clerks were employed by various institutions at this time. This situation continued until the end of 1926, when there was a revolution of sorts in December. Nationalistic Lithuanians (Tautininkai) politically took control of Lithuania, abolishing the democratic state of the municipalities. They also abolished special rights for national minorities in the municipalities and limited their representation in the ruling order. To limit the power of the Jewish population, the Lithuanians annexed villages and isolated suburbs that were populated by Lithuanians under the municipality of Kovno. The overall percentage of Jews in the town population therefore decreased. The mayor of Kovno became Vokietaitis; he was later succeeded by Markys. A spirit of fierce patriotism now spread through Lithuania and anti-Semitism took root in the offices of the local administration. The nationalists tried to uproot the established Jewish financial institutions in town, limiting the contribution to Jewish educational institutions as well as decreasing cultural assistance for the Jews. They also limited the number of working clerks of Jewish background. The nationalists’ aim was to underscore and abolish the influence of the Jews in town, a town where at least 25% of the population was Jewish, and the share of the economy contingent upon Jews was greater than even that. During this period, the Jews who were still active in the municipality included Doctor Meschulman Wolf, the attorney Ruven Rubinstein, Jacov Roginski, Leon Ozineski, David Itzkuvitz and Eli Hadash. Ruven, son of Don Rubinstein, was born in Otian in 1891. He studied in the Hebrew gymnasium in Vilna, later studying law in St. Petersburg. From early youth, he was a member of the Zionist movement and editor of various Zionist papers. In between 1920 and 1923, he was the legal advisor of the Lithuanian embassy in Moscow, helping many exiled Jews return to Lithuania. Starting in 1923, he was editor of the Yiddische Stimme, and spoke regularly on the Kovno radio on Jewish subjects. He was a member of the municipal committee of Kovno, and representative in the Zionist congress. In July 1940, when the Soviets entered Lithuania, he was sentenced to eight years of prison in Siberia. His family perished in the Kovno ghetto; he arrived in Germany in 1946 and eventually immigrated to Tel Aviv, where he died in 1967.

The Cultural and Financial Life of the Jewish Community

According to the census of September 17, 1923, Kovno’s Jewish population at this time numbered 25,044, which was 27.1% of the general population. In the year 1933, the Jewish population compromised 38,000, or 29.8% of the general population. Truthfully, the Jewish population decreased during the period of interwar Lithuanian independence, both in absolute and relative numbers. Nevertheless, the Jewish community reached its apex as far as spiritual, economical, and social prominence. The Jews of Kovno, as the rest of the Jews of Lithuania, fought adamantly to keep their financial standing despite the fact that they had relinquished their prominent positions in certain industries, such as those concerning agricultural, raw materials, livestock, and harvest products. They were still able to keep their control in the commerce of textile, building products, the lumber industry, and, particularly, the import of industrial products.

The energetic and take-charge spirit of the Jewish community found an outlet for expression in the industrial world, and Jews became very successful. Due to their talents and international connections, the Jews were able to run successful industries both in the town and its environs, and were assisted by the government, which wanted to decrease its dependence on imported goods. With the help of the foundation, corporate Jewish banks were opened; the central Jewish bank assisted in petty commerce and Jewish trade.

The lifestyle of the working Jewish population was elevated and improved, and a newly-established wealthy Jewish class now formed. The Jews used their income to further their industry; this was a period of burgeoning in all fields of public life. New schools were established, as well as gymnasiums, banks, newspaper industries, and others. The Jews’ educational institutions included a nursery school, elementary schools, professional schools, five high schools, two teacher seminaries, yeshivas, and even a community university that was managed by Doctor Ester Elyashiv. The language of instruction was Hebrew, both in the schools established by Tarbut and religious schools established by Yavne. In 1940, 500 out of 3401 Lithuanian University students were Jewish.

There were a few daily newspapers in Yiddish in Kovno, amongst them Yiddische Stimme, whose first editor was Leib Garfunkel, followed by Moshe Kohen and, in 1923, Ruven Rubinstein. This paper, the oldest and most prominent among all the Jewish newspapers in Kovno, was founded in 1919. There was also Folksblatt, the first editor of which were Doctor Mondel Sudarski and Judel Mark; Das Wort, edited by Nathan Goren and Efraim Greenberg; Mament, and others. In addition, there were a few libraries, the most prominent amongst these being the Mapu library and that of Knowledge-Seekers (Lieber von Wissen). A drama studio was run in Hebrew near the Tarbut center, and a popular theater in Yiddish was managed by Lan. Amongst such social establishments we should mention the children’s home, founded by Doctor Leman, a ‘health home’ of AZE, a large Jewish hospital, an orphanage named for Ytzhak Elhanan Spektor that was managed by Tuvia Shapiro, Dotor Aba Lapid, Isa Rabinovisch, and Yosef Margolin. There was also a home for the elderly. Some of these Jewish institutions were established in upscale new buildings. Such edifices contained the two Hebrew gymnasiums, the central bank, the children’s home, the ‘health home’ of AZE and others.

Most of the Jewish youth congregated in Zionist movements like Hashomer Hazayir, Beitar, the Zionist youth, majakiva, Gordonija, and the ZS. There were student unions and sports unions like Makaby, Hapoel, and others that developed sophisticated educational systems and trained young Jews for immigration to and agricultural life in Israel. The Chalutz opened a training kibbutz in the town, which included the corporate carpentry of the Chalutz, managed by A. Shragovic. The activities of the left were limited, both because it had little influence on the community and because it was officially forbidden for many years. The communist left came out from underground only when the Soviets invaded and occupied Lithuania in 1940. That year, all the educational and cultural institutions of the Jews were transferred to the control of Communist Jews.

In Jewish Kovno, during the independent Lithuanian period, there was a public cultural struggle of cultural leaders and artists, both residents and from abroad. During these years, there were many authors and big businessmen who settled in Kovno temporarily on the way from the Soviet Union to Western Europe or to Israel. Authors, poets, and public servants from the land of Israel and other countries would often visit Lithuania, amongst them famous poets like Byalik and Chernikovski, politicians like Zalmand Schneo, Nachum Sokolov, or Siskin Zabotinksi, Ben Gurion, Birenbeim, Dubnov, AZ Greenberg, A Steinman, Y Lamden, D Bergelson, and CH Zitlovski. The effect of their visits in Lithuania lasted for a long time. The cultural and social activities in independent Lithuania mark a very important chapter in the history of Jews in Eastern Europe. In the history chapter of the inter-war years, Jewish Kovno occupies splendid pages.

On August 15, 1941, there were about thirty thousand Jews enclosed in the ghetto in Slobodka or Viliyampole. Most of these Jews were annihilated during the following years of Nazi occupation. Viliyampole, which was the cradle of Jewish Kovno in the 15th century became, during those years, its cemetary. Abruptly, like this, came the end of six hundred years of culture and life on the shores of the Vilya.

Rabbis of Kovno

Rabbi Azriel, son of Rabbi Jahudah

Rabbi Juri Saksh

Rabbi Moshe Chalevi Solovecik

Rabbi Josef, son of Rabbi Moshe Solovecik

Rabbi Menachi Mendel Rabinovich

Av-beit din of Kovno (religious judges)

Rabbi Ariel Leib, son of Menachem Zundel Shapiro

Rabbi Moshe Ytzhak Avigdo, son of Schmuel

Rabbi Joshue Leib Diskin

Rabbi Ytzhak Elhanan Spektor

Rabbi Tsvi, son of Ytzhak Elhanan Rabinovich

Rabbi Avraham Dubar, son of Salmand Sander Shapiro

Other Religious Leaders

Rabbi Moshe, son of Rabbi Elyahu

Rabbi Avraham, son of Ravi Moshe Sackheim

Rabbi Ariel Dikes

Rabbi Ytzhak Ornovski

Rabbi Israel Nisan Krek

Rabbi Gershon Gutman

Rabbi Bylitski

Rabbi Israel Rosensohn

Rabbi Simha Gitlevitz

Rabbi Smitarm

Rabbi Ytzhak Solovecik

Rabbi Ruvenschnitkind

Rabbis of Slobodka

Rabbi Uri Saksh

Rabbi Eliyahu from Ragula

Rabbi Jacov Eliyahu Segal

Rabbi Gavriel Feinberg

Rabbi Moshe, son of Mejir Danischevski

Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein

Rabbi Shlomo Salmand Osovski

Rabbi Josef Zusmanovich, aka The Man of Jerusalem

Rabbi Moshe Skarota

Heads of Yeshiva

Rabbi Israel Salanter

Rabbi Israel Salmand Mencher

Rabbi Tsvi Hirsch Levitan ( great grandfather of husband of translator)

Rabbi Ruven Miltski

Rabbi Baruch Dov Leibowitz

Rabbi Jacov, son of Israel Katz

Rabbi Avraham Aaron Burstein

Rabbi Yosef David Berger

Rabbi Chaym Shalom Tuvya Rabinovitsch

Rabbi Naftali Tsvi Trup

Rabbi Ytzhak Jacov, son of Schmuel Rabinovitch

Rabbi Schlomo Nathan Kotler

Rabbi Nette Tsvi Finkel

Rabbi Yosef Ben Zion Friedman

Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein

Rabbi Eliyahu Bar Leizerovitch

Rabbi Gershon Gutman

Rabbi Baruch Horowitz

Rabbi Ytzhak Isac Sher

Rabbi Shraga, son of Baruch Horotwitz

Rabbi Ytzhak Isac Elizer Hirshovitz

Rabbi Shmuel Chaim Jancok

Rabbi Ytzhak Melzer

Rabbi Tsvi Schneider

Rabbi Jacov Pakelniski

Rabbi of Alksot

Rabbi Avraham, son of Aaron Shenker

Rabbi Shmuel Jacov Rabinovitch

Rabbi Baruch Horowitz

Rabbis of Carmelita

Rabbi Margalit

Rabbi Aaron Breudo

Rabbis of Sanci

Rabbi Slant

Rabbi Moshe Jacov Shmukler

Public Servants

Leon Oziniski

David Ilgovski

Karlman Aip

Arie Intriligator

Doctor Elhanan Elkes

Doctor Benjamin Berger

Boris Bernstein

Aba Blosher

Doctor Benjamin Bludes

Leiv Garfunkel

Shmuel Goldberg

Attorney Jacov Goldberg

Nathan Greenblech Goren

Doctor Elhanan Dobrowitz

Doctor Ytzhak Elfael Holzberg

Doctor Meschulam Wolf

Tsvi Gregory Hans Wolf

Attorney Schlomo Horonzitski

Salmand Trakinisheski

Noah Jofe

Helena Chezkels

Moshe Kohen

Doctor Aba Lapin

Doctor Ytzhak Levitan

Doctor Levin

Yosef Margolin

Doctor Moshe Matis

Ana Matis

Rabbi Shlomo Muncher

Doctor Menachem Solovechik

Leoneti Solovechik

Matityahu Solovechik

Doctor Mendel Sudarski

Alter Sudarski

Eliyahu Salomon

Attorney Ozer Finkelstein

Doctor Lazar Finkelstein

Doctor Shmuel Elyashiv Friedman

Tsvi Port

Ytzhak Kopilovich

Doctor Kerber

Yosef Raginski

Rabbi Israel Rosensohn

Rabbi A. Rodner

Isar Rabinovich

Felix Rabinovich

Shulamit Rabinovich

Jacov Rabinsohn

Ruven Rubinstein

Doctor Elazar Rachmilevich

Doctor Nachman Rachmilevich

Doctor DM Schwartz

Israel Strasburg

Ytzhak Streichman

Ytzhak Schmuelovich

Tuvja Shapira

Shmuel Seider Serchevski

Natives of Kovno – Religious Personae

Johnathan, son of Rabbi Mordechai Aliashberg

Jacov David, son of Jehudah Gordin

Asher Livman, son of Shcmuel Israel Zrahi

Tsvi Hirsch Levitan

Kelman, son of Rabbi Eliezer Magid

Yosef, son of Mosche Halevi Solovechik

Samon Yitzhak, son of Yehudah Tsvi Halevi Finkelstein

Tsvi Farber

Tsvi Peisah, son of Jehudah Leib Frank

Schlomo Nathan Kotler

Tuvia, son of Yosef Gefen

Eliezer Simha, son of Menahe Mendel Rabinovitch

Schmuel Moshe, son of Ariel Leib Shapira

Schlomo Pinskhas, son of Moshe Schmuel Batnitski

Yehudah Dov, son of Nathan Bernstein

Schrage, son of Baruch Horowitz

Schmuel Ytizhak, son of Tsvi Joffe

Yosef Tsvi, son of Avraham Alevi Kahlmans

Other Notable Citizens

Paul Ebelson, lawyer and advocate

Schahnah Avramson, lawyer and representative in the Duma

Chaiman Inilov, researcher

Isidor Elieshiv (Fridman), author

Ester Elieshiv, author

Dora Askovich, author

Yehezkel Epstein, rabbi and researcher

Mordechai Epstein, economist

Israel Bytan, researcher

Herald Berman, editor and translator

Leon Bramson, attorney and public personality

Moshe Bramson, revoltutrionary

Yehudah Dov Bernstein, rabbi and engineer

Julius Blumenthal, editor

Joshua Gordon, activist in Israel

Emma Goldman, anarchist and feminist

Levi Ginsburg, reknowned researcher of Jewish Studies

Nathan Greenstein, chemist

Israel Luis Dublin, statistician

Ytzhak Dambor, physician and public activist

Yehezkel Dilion, leader of Beitar

Ytzhak Donski, author and political activist

Bernard Horowitz, banker and Zionist activist

Mordechai Alperen, Zionist activist and businessman

Nehemya Hofman, journalist

Salmad Vilk, Zionist activist

Abraham Vladstein, author and activist in the Zionist labor movement

Meschulem Wolf, political activist

Tsvi Gregory Hans Wolf, activist

Arnold Walper, conductor

Chaim Aryazuta, author and pedagogue

Lois Satenstein, indusstrialist

Moshe Zejev Sohn, pedagogue and Zionist activist

Shalom Yosef Silberstein, researcher

Menachem Zlatsberg, author

Yehudah Leib Japo, businessman and author

Mordechai Jetkonski, businessman

Reuven Leon Kohen, bacteriologist

Helene Chatzkels, pedagogue

Avraham Moshe Lunz, researcher of the land of Israel

Eliezer Daniel Lakson, journalist

Yehoshua Levinson, author

Nachum Levinski, from the leaders of Bund

Avraham Mapu, Hebrew author

Miriam Mosensohn, author

Pinkhas Mordel, linguist

Irvine Miller, rabbi and Zionist activist

Oskar Minkovski, endocrinologist

Herman Minkovski, mathematician

Julius Matz, pathology of plants

Shmuel Markel, religous activist

Arie Mapu, physician

Hirsch Neviezer, public activist

Benjamin Zajef Neviezer, head of the community

Mark Nathanson, anarchist

Leon Svoig, lawyer and journalist

Aba Solovechik, one of the originators of the Jewish community and donor toward community

Menachem Solovecik, activist and researcher of biblical studies

Matiyahu solovecik, activist

Yente Soldecki, author

Benjamin Faibelson, artist

David Feinberg, activist

Ozer Finkelstein, attorney and activist

Yosef Shlomo Frinovic, author

William Kaiser, Yiddish poet

Yekutiel Kissin Nigrunicki, author

Yehudah Leib Kalivanski, activist and Zionist

Avraham Kaplan, author

Lazar Krestin, artist

Shlomo Kalson, activist

David Krano, engineer

Aaron Karon, pedagogue

Ytzhak Rabinovich, the Man of Kovno, poet

Lydia Rabinovich Kempner, bacteriologist

Herman Rabinovich, rabbi

Yihayahu Rosenberg nee Karl Fonberg, author

Anna Rapoport, author

Isar Rabinovich, activist

Benjamin Rabinovich,

A.S. Schwartz, physician and poet

Moshe Aaron Shmalicenski, one of the first Zipnist

Ruven Schnitkind, rabbi

Yehudah Eidel Shorshevski, researcher of the Talmud

D.M. Schwartz, physician and public activist

Bibliography

Pinhkas Medinat Litva (The Jewish Books of the State of Lita)

The Scroll of Kovno (Megilat Kovno)

D.M. Lipman, The History of the Jews of Kovno and Slobodka

Jacov Livschit, Zihron Jacov, part A

Professor Janolaitis, The Jews of Lita (in Lithuanian)

Newspaper Yiddishe Stimme, edition 53586

Bericht von der Yiddishe Seim, Fraktien in den Litauischen Seim, 1925-26

Jewish Encyclopedia

Jewish Universal Encyplopedia Minor

Encyclopedia Eshkol, in German

Russki Hebrais Encyclopedia

Britich EncyclopediaKOVNO view_friendly.jsp?artid=387&letter=K(print this article)

By : Herman Rosenthal

ARTICLE HEADINGS:

In the Sixteenth Century.

In the Eighteenth Century.

The Kovno Megillah.

Philanthropic and Charitable Institutions.

Jewish Artisans.

Russian fortified city in the government of the same name; situated

at the junction of the Viliya and the Niemen.

There is documentary evidence that Jews lived and traded in Kovno toward

the end of the fifteenth century. At the time of the expulsion of the

Jews from Lithuania by Alexander Jagellon (1495) the post of assessor

of Kovno was held by Abraham Jesofovich. By an edict dated Oct. 25,

1528, King Sigismund awarded to Andrei Procopovich and the Jew Ogron

Nahimovich the farming of the taxes on wax and salt in the district

of Kovno ("Metrika Litovskaya Sudebnykh Dyel," No. 4, fol.

20b). In the Diet of 1547 a proposition was submitted to the King of

Poland to establish at Kovno, Brest-Litovsk, Drissa, and Salaty governmental

timber depots, in order to facilitate the export of timber, and to levy

on the latter a tax for the benefit of the government. This measure

found favor owing to the claim that the Jewish and Christian merchants

of Kovno and of other towns derived large profits from the business,

while they at the same time defrauded the owners of the timber and encouraged

the destruction of the forests. The proposition was adopted by the Diet

and sanctioned by the king ("Kniga Posolskaya Metriki Litovskoi," i. 36).

In the Sixteenth Century.

In 1558 a Jew of Brest-Litovsk, David Shmerlevich, and his partners

obtained a monopoly of the customs duties of the city of Kovno on wax

and salt for three years, for an annual payment of 4,000 kop groschen

("Aktovyya Knigi Metriki Litovskoi, Zapisi," No. 37, fol.

161). David of Kovno, a Jewish apothecary, is mentioned in a lawsuit

(Oct. 20, 1559) with Moses Yakimovich, a Jew of Lyakhovich ("Aktovyya

Knigi Metriki Litovskoi Sudnykh Dyel," No. 39, fol. 24b). By an

agreement of about the same date between Kusko Nakhimovich, a Kovno

Jew, and Ambrosius Bilduke, a citizen of Wilna, it would seem that the

latter had beaten and wounded the Kovno rabbi Todros, and that Kusko,

in consideration of 2 kop groschen, had settled the case and was to

have no further claim against Bilduke (l.c. No. 41, fol. 120).

From a decree issued by King Stephen Bathori Feb. 8, 1578, it is evident

that Jews were living in Kovno at that time ("Akty Zapadnoi Rossii,"

iii. 221). Another document (June 19, 1579), presented to Stephen Bathori

by the burghers of Troki, both Catholic and Greek-Catholic, and by the

Jews and Tatars, contains their petition concerning the Christian merchants

of Kovno, who had prohibited the complainants from entering the city

with their merchandise, and from trading there; this in spite of the

fact that the burghers of Troki had from time immemorial enjoyed the

privilege of trading in Kovno on an equality with the other merchants,

both Christian and Jewish, of the grand duchy of Lithuania. In reply,