Sharett Family |

|

Click

on Photos to Enlarge |

|

#shar_01: |

#shar_02: |

#shar_03: |

#shar_04: |

#shar_05: |

#shar_06: |

#shar_07: |

#shar_08: |

Shertok/ Sharett family

For family tree go to: http://www.geni.com/people/Yaakov-SHERTOK/6000000000890391275?through=6000000006861936269

Yaakov and Fania with their oldest

children ( Rivka and Moshe)

Yaakov and Fania with their oldest

children ( Rivka and Moshe)

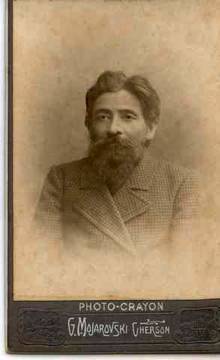

A native of Pinsk, Yaakov Shertok ( May 10, 1860- March 8, 1913) was the father of Moshe Sharet.

Yaakov Shertok

Yaakov Shertok

Yaakov was a member of BILU (Heb.

בִּיל״וּ, Hebrew initials of

Beit Ya'akov Lekhu ve-Nelkhah; "House of Jacob, come ye and let us

go," Isa. 2:5), an organized group of young Russian Jews who pioneered the

modern return to Ereẓ Israel. Bilu was a reaction to the 1881 pogroms in

southern Russia, when the ideology of Jewish nationalism began to replace that

of assimilation, which was prevalent among the youth. At first not linked with

any particular country, the Bilu ideology soon came to mean a return to

Ereẓ Israel. One of the first Bilu'im,Ḥayyim *Hisin , testified:

"The recent pogroms have violently awakened the complacent Jews from their

sweet slumbers. Until now, I was uninterested in my origin. I saw myself as a

faithful son of Russia, which was to me my raison d'étre and the very air I

breathed. Each new discovery by a Russian scientist, every classical literary

work, every victory of the Russian kingdom would fill my heart with pride. I

wanted to devote my whole strength to the good of my homeland, and happily to

do my duty, and suddenly they come and show us the door, and openly declare

that we are free to leave for the West."

In Eretz Israel

The first to arrive in the country was Ya'akov Shertok , who preceded the first

group of 14 Bilu'im by a few weeks. The group, led by Belkind, reached Jaffa on

July 6, 1882.

Yaakov returned to Russia after failing to adapt to agricultural labor. In 1906

he immigrated to Israel with his family and brother, and settled in the Arab

village of Ein Sinia, between Jerusalem and Nablus. In this environment, his

children learned Arabic and Arab customs.

In 1910 the family moved to Jaffa/ Tel Aviv

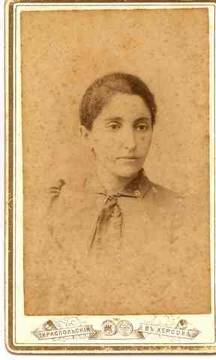

Mother:

Fania Shertok nee Lev

Mother:

Fania Shertok nee Lev

The Lev Sisters

The Lev Sisters

Son of Yehuda Leib Shertok and Yehudith Chertok,

Husband of Fanya Shertok nee Lev

Rivka Hoz ( sitting on the right),

Moshe Sharett, 2nd Prime Minister of Israel ( standing on the

left), , Ada Golomb (standing on the right)), Yehuda Sharett (

sitting at the bottom) , Geula Shertok ( with her feet up).

The oldest daughter: Rivka, was married to Dov Hoz:

Dov Hoz (1894-1940) was a leader of the Labor Zionism movement, one of the

founders of the Haganah organization, and a pioneer of Israeli aviation.

Born in Orsha, Russian Empire in 1894, Hoz immigrated to Ottoman Palestine

along with his family in 1906.

Beginning in 1909, he was part of the group that organized guarding activity of

the city of Tel-Aviv. The group included Shaul Meiruv-Avigor, Eliyahu Golomb

and Moshe Sharett.

During World War I, Hoz volunteered for service in the Turkish army and was

sentenced to death for continuing activities to secure the Jewish settlement of

Palestine. He escaped death by fleeing to the south of Palestine which had just

been conquered by the British.

Some highlights of his career:

He was one of the organizers of the Jewish Legion.

1920-1930: Member of the central Haganah committee

1931-1940: Member of the national Haganah command center.

One of the heads of the labor movement and part of the group that start the

socialist Ahdut HaAvoda party.

1935: Appointed vice-mayor of Tel-Aviv.

Later, head of the state department of the Histadrut (Labor Federation).

Founder and CEO of "Aviron", a company which pioneered aviation in

Israel, mostly for security purposes, by training pilots, establishing flight

lines in Israel and outside. This company served as cover for "Sherut

Avir" of the Haganah.

Hoz died in a car accident in December 1940 on his way to an Aviron board

meeting. In his car were his wife Rivka (sister of Moshe Shertok later to be

known as Moshe Sharett, making Sharett Dov's brother-in-law), daughter Tirza,

sister in law Tzvia Sharett and business partner Yitzhak Ben Yaacov.

Kibbutz Dorot in the Negev is named after the Hoz family members to denote

"Dov, Rivka, Tirza".

Sde Dov Airport in North Tel-Aviv is also named after Dov Hoz.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dov_Hoz"

Tamar Gidron (Hoz)

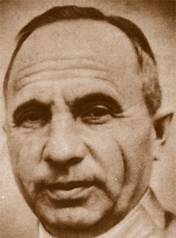

Moshe Sharett on 15 October 1894, died 7 July 1965 was the second Prime

Minister of Israel , serving for a little under two years between David

Ben-Gurion's two terms.

Born in Kherson in the Russian Empire , Sharett emigrated to Ottoman-controlled

Palestine in 1906. In 1910 his family moved to Jaffa, and they became one of

the founding families of Tel Aviv. He graduated from the first class of the

Herzliya Hebrew High School. He then went off to Istanbul to study law at the

University of Kushta , the same University Yitzhak Ben-Zvi and David Ben Gurion

studied at. However, his time there was cut short due to the outbreak of World

War I. He subsequently served as a 1st Lt., interpreter in the Turkish army.

After the war he worked as an Arab affairs and land purchase agent for the

Assembly of Representatives of the Yishuv. He also became a member of Ahdut

Ha'Avoda and later of Mapai. In 1922 he went to the London School of Economics,

and while there he actively edited the "Workers of Zion". He then edited

the Davar newspaper from 1925 until 1931. In 1931, after returning to

Palestine, he became the secretary of the Jewish Agency's political department.

In 1933 he became its head, and he held that position until the formation of

Israel in 1948.

Sharett was one of the signatories of Israel's Declaration of Independence. He

was first elected to the Knesset in 1949, and served as Israel's first Minister

of Foreign Affairs. In this role he established diplomatic relations with

dozens of nations, and got Israel into the UN. He held this role until 1956.

Herzliya Hebrew High School's first class photo with Dr. Metman Cohen. First

row on the back, from the right: Behrav, Yitzhak Cohen-Kedmi, Hannah Chon,

Nehama Friedman, Yona Papo, Moshe Shertok (Sharett), Zerubavel Habib; second

row, from the right: Alexander Malchi, Eliyahu Golomb, Beit Halahmi, Ginsburg,

Rivkah Shertok (Hoz), Tzila Feinberg, Matityahu Gruno, Dov Hoz; third row, from

the right: Carmi (Janovsky) Berman, Kavshana, Wolfson, Dr. Metman-Cohen, Penny

Metman (sitting down), Nahum Rzenik (sitting down), Chaya Weiss; sitting, from

the right: Menuchin, Vinokor, Kleinovich, Milotzky

Daughter Ada married Eliyahu Golomb

(born 2 March 1893, died 11 June 1945) was the leader of the Jewish defense effort in Mandate Palestine and chief architect of the Haganah, the underground military organization for defense of the Yishuv between 1920 and 1948.

Golomb made aliyah to Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire, from his home in Vawkavysk in the Russian Empire (today in Belarus) in 1909. He initially organized agricultural training courses and worked in kibbutz Degania Alef. When World War I broke out in 1914, Golomb opposed the enlistment of Jews as officers in the Ottoman Army and instead insisted on the creation of an independent Jewish defense force. In 1918, he became a founder of the Jewish Legion which he hoped would form the basis of a permanent official Jewish militia. After his demobilization he became a member of the committee entrusted with organizing the Haganah and in 1920 was active in sending aid to the defenders of the northern outpost of Tel Hai.

Haganah

Golomb was instrumental in the development of Jewish self-defense forces. He claimed that the Jewish masses must be mobilized into fighting units capable of defending Zionist goals. Golomb was a founding member of the Haganah and served on its Command Council. He traveled extensively, purchasing arms for Haganah fighters. The organization and financing of illegal Jewish immigration in the late 1930s was in large part directed by Golomb.

Golomb saw the Haganah as an integral part of the Zionist movement, and thus objected to the existence of more radical defense organizations, such as the Irgun. He strongly disagreed with those who supported indiscriminate attacks against Arabs. At the same time, he did advocate active confrontation with Arab aggressors. Along with Berl Katznelson, Golomb spent much time working with Ze'ev Jabotinsky of the Revisionist party trying to unify defense efforts among Jews. Golomb's home in Tel Aviv was later converted into a museum of the Haganah named Beit Eliayahu.

Golomb opposed the view that defense should depend on a small elite, and instead insisted that it was the concern of the Jewish population at large. In 1922, he was sent abroad to purchase weapons for the Haganah and until 1924 organized pioneering youth in Europe. During the Arab riots of 1936-39, Golomb was one of the initiators of the Fosh, units that confronted Arab fighters in combat.

Although supporting Jewish enlistment in the British Army during World War II and the parachuting of Jewish agents into Nazi-occupied Europe, Golomb never forgot the necessity for the removal of the British mandatory power from Palestine. He became a founder of the Palmach, the commando arm of the Haganah and foundation of the Israel Defense Forces, and trained many of its future commanders.

He died in 1945 at the age of 52. His son David later served as a member of the Knesset.

"I'm continuing my father's path,

exactly that," Dalia says…... "Our paths are not contradictory. I

have acquaintances who ask me how I, the daughter of the 'founder of the

Haganah, do what I do, and I say that's exactly the point. My father founded

the Haganah (defense), not the occupation. The Haganah, which became the IDF,

was intended to defend the country, but over the years the army turned into the

Israel occupation forces. My father, were he alive, would have been horrified

by that. He was unusually sensitive to human dignity and he would have suffered

at seeing sights such as those I'm seeing here and now. I'm sure that he would

have felt bad in this place, just as I do. But perhaps he would have changed

something that I can't change although I would like to. He had more power than

I have."

For six years Golomb has devoted her energies

to MachsomWatch, a group of Israeli women who monitor IDF treatment of

Palestinians at Israeli checkpoints, visiting checkpoints throughout the West

Bank with her friend, organization spokeswoman Raya Yaron. She uses a small

video camera to film the testimony of laborers about their most recent

experiences at the checkpoint, and Raya writes down every word. They then issue

a joint report, with which they approach the military, human rights

organizations and judicial bodies in a vain attempt to put an end to these

injustices. They already have hundreds of hours of filmed testimony and they

don't want to stop, fearing that if they do no one will step into the resultant

vacuum.

Conciliation track

In addition to being the daughter of the

Haganah's founder, who died 64 years ago next week, Golomb is also the niece of

Israel's second prime minister, Moshe Sharett. He was the brother of her

mother, Ada Shertok: "There are two tracks in this country. There's an

aggressive track, which occupied the country and took control of it; and

there's the track of conciliation and a desire to live together. That's the

track of my uncle, Moshe Sharett, who was a conciliatory and considerate person

who wrote in his book that he hoped that if we receive reparations from the

German government for the deeds of the Nazis, we would be able to pay compensation

to all the Arabs we exploited. He was the only one to voice such words. I

haven't heard other such voices. [Israel's first prime minister David]

Ben-Gurion didn't think that way, and because Sharett did not continue to lead,

but rather the aggressive side, we have arrived at our current situation."

Golomb has two children, from her marriage to

Labor politician Asher Yadlin: Law professor Omri Yadlin and choir conductor

Anat Morag. In October 1976, just a few days before he was slated to be appointed

governor of the Bank of Israel, Asher Yadlin was arrested for bribery,

embezzlement and income-tax evasion stemming from a previous public

appointment. He was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison. The couple

divorced during this period and Dalia went back to her maiden name, Golomb.

She began her activity in MachsomWatch at the

height of the second intifada: "I felt bad about the situation with the

Arabs because I was educated to great friendship with our neighbors. Even when

I began at the checkpoints I wasn't afraid for a moment of nationalist

incidents." She calls the soldiers who staff the checkpoints "victims

of the occupation, just like the Palestinians."

"They're really unfortunate, and they

understand that only after their discharge. The tremendous power given to a boy

of 18 is heady. When I speak to them about the occupation they say that they

are here because of security constraints. That's also what they said when they

operated the Beit Iba checkpoint, near Nablus. Suddenly, when [U.S. President

Barack] Obama's sun rose in our skies the checkpoint was suddenly closed, after

many years, as though something had genuinely changed," she says.

The parking area on the Israeli side of the

Eyal Crossing is full of commercial vehicles belonging to Israeli employers who

have come to pick up their workers. The Palestinians who have passed through

security hurry down the path to their ride. Their faces are expressionless and

there is little conversation between them. Several stop next to Golomb and

Yaron, who they know from innumerable past shifts.

"We've been here since 4 P.M.,"

says Golomb. "The line was horrifying. About 5,000 people. There are eight

security positions but for some reason only four are open. Yesterday there were

only two. The fewer the booths the longer the line, and then terrible riots

erupt when people push because they're afraid to miss a day of work. They know

that if they're late their Jewish employer won't wait for them and they'll

return home disgraced and humiliated. Not only won't they earn money that day,

they'll even lose money."

The Palestinians tell of bruises resulting

from the pushing and crowding at the checkpoint. Sometimes, one says, the

soldiers use teargas to control the crowds. One of the Palestinians pulls out a

cell phone and shows a video clip several seconds long that he filmed until he

was forced to flee by the effects of the gas. The clip shows dozens of his

friends retreating while thick smoke covers the area. Golomb and Yaron ask him

to send them the clip, but he and his friends refuse to do so, or to give their

names.

"I admit, I'm afraid of the army,"

one says. "I'm afraid that if I criticize the soldiers, tomorrow morning

they won't let me through. I have a wife and children to support." Another

says that a few days ago a workmate died as a result of the crowding at the

crossing and another acquaintance broke a leg while hurrying to get a better

place in line.

Within this chaos, a tired soldier approaches

the fence between the checkpoint and the parking lot. He is looking for Jews,

and finds the grannies from MachsomWatch. He asks for a favor: He's hungry and

would like them to buy him a cookie from the canteen, about 200 meters away.

"Don't they feed them in the army?" wonders Golomb, as she makes her

way to the vendor. She had surgery on her leg a few weeks ago. She has to

disappoint the soldier because the cookies ran out and only coffee and tea are

available. "Never mind, I'll manage," answers the soldier in

embarrassment.

"I feel like the representative of the

State of Israel here, and in its name I try to beautify the ugliness of the

occupying Israelis. I want to show that there are also other Israelis, that

even within all this occupation we see the Palestinians, that they are not

invisible," says Yaron, who recently turned 70. She has been active in

MachsomWatch for five years. She says she feels crushed when Israeli soldiers

and civilians accuse her of being a "traitor" or

"Jew-hater."

"Go tell these people that my father,

Eliyahu Carmieli, was one of the builders of the country, one of the founders

of Kibbutz Ginegar on the shores of Lake Kinneret, who served as the head of

the first regional council in the Jezreel Valley," says Yaron.

"This is the only way we have,"

says Golomb. "We have almost no influence. We are only 250 women from the

entire country. Where is everybody? And still, all the human rights movements

in the world were created precisely because of these intolerable human

situations. We really have no other way."

Life's dreams and woolen socks

In addition to shedding light on the history of the Zionist movement and his own personality, the letters of Moshe Sharett also show that the conflict with the Palestinians was the same then as it is today.

By Tom Segev

Moshe Sharett: The London Days Letters, 1920-1921," The Association to Commemorate Moshe Sharett, 520 pages, NIS 95

In the summer of 1920, a girl named Rosa arrived in Palestine. She came from Russia, as did nearly everyone in that period. Moshe Shertok, also a native of Russia, gave her a letter of recommendation: She is "an important young lady," he wrote to his sister Ada. Indeed, Rosa Cohen came from Berl's hometown and Katznelson himself even knew her personally. Shertok thought it was very worthwhile to encourage her to remain in the country and instructed his sister to devote special attention to her: "She hasn't seen a Jewish face for years," he wrote, "and now she is afraid of this. She also has fears about communal living, to which she is not accustomed. For her, the Cohen house is suffocating - you know the type of intelligent Russian girl from the haute bourgeoisie who has broken off all connection with her family and her society and can't stand them any more."

Cohen was not a Zionist. "She is very far from everything we are involved in," as Shertok wrote, and she "just happened" to find herself in Palestine, according to him. Apparently she had actually intended to immigrate to the United States. By chance she met a group of people who were sailing for the Land of Israel on the ship Ruslan, and for some reason decided to join them.

The Ruslan was a kind of Zionist Mayflower: Many of its passengers became mothers and fathers of the Hebrew elite in the Land of Israel. Rosa was the niece of the writer and activist Mordecai Ben Hillel Hacohen, the patriarch of a dynasty that includes a number of well-known figures including a chief of staff, Yigal Allon, and a number of Israel Defense Forces generals. Rosa Cohen married a man named Nehemiah Rabin, and their first-born son was Yitzhak.

The letters that Shertok sent during that period from London reveal, among other things, a huge romantic drama that could serve as the basis for a Zionist telenovela: His sister Rivka found it difficult to make up her mind as to which of two boyfriends she would love more, and finally chose Dov Hoz; the other one, Eliyahu Golomb, got her sister Ada. Shertok himself married Zippora Meirov, who was the sister of Shaul Avigur - a founder of the Labor Movement in the Land of Israel and of the security establishment.

There are streets named after these people, but many of them, perhaps even Shertok himself, have been nearly forgotten. He changed his name to Sharett and served as the first foreign minister and as the second prime minister of Israel.

Diplomatic restraint

Shertok-Sharett wrote a great deal during his lifetime and his writings, among them the diaries and the letters, reflect the history of Zionist movement and the struggle for the establishment of the state. In general he was not strong enough to stand up for his opinions and he often did not dare to do this; therefore, he ultimately was also not that important a figure. In fact, it is possible that the most important thing Sharett contributed to the state is the personal diary he wrote during his tenure as prime minister. It is difficult to overstate the importance of those eight volumes to the study of the 1950s and to the understanding of Israeli history as a whole. This is a debt that Israel also owes to his son Yaakov, who saw to the publication of his father's diary. He is also one of the editors of this volume.

Some of the letters that the student Shertok wrote at the beginning of the 1920s are quite interesting, in part because they reflect some of the aspects of the personality that peek out of the diaries that prime minister Sharett kept during the 1950s. When he went to study law at the London School of Economics, Shertok was about 26. The English method of teaching left Shertok bored "to the point of nausea" and he quickly preferred to get involved in the work of the Zionist movement. "I know that my life will be political activity. This is inevitable," he wrote even before he left. In London he found himself a partner to the effort to raise funds, purchase arms and make political contacts with the Palestinians.

During his stay in London, the first acts of terror in Palestine began, initiated by Palestinians against the Zionists. One of those killed was the writer Yosef Haim Brenner. Shertok was overwhelmed with grief at this "holocaust," as he wrote: "I wept like a child, like after the death of a father." Later Sharett became known for his diplomatic restraint, in contrast to the military activity led by David Ben-Gurion, but when he heard about Brenner's murder, he wrote: "There have to be hangings and hangings. Just hangings." These early incidents instilled in the consciousness of the Zionist movement the almost deterministic sense that Palestinian terror has to be seen as a permanent and inevitable factor.

Sharett's letters also show that the conflict of his day is also the conflict of our own day. Shertok was present as an interpreter at a discussion that was held between Chaim Weizmann and the first leader of the Palestinian national movement, Musa Qassem al-Husseini, and when it was over he wrote: "It was interesting, but no results. No results at all." Elsewhere he wrote: "Nothing came of it, and apparently nothing will." His letters transmit a sense that the public in the Land of Israel can rely only on itself.

The first donations for the acquisition of weapons were obtained by Ze'ev Jabotinsky. Everything was secret, and it was even forbidden to report on it to David Ben-Gurion because Ben-Gurion, wrote Shertok, was "a miserable person, who has no control over his tongue." Even then, as he was taking his first steps in a movement that itself was only just starting out, Shertok encountered all-embracing personal intrigues and immortalized them in a rush of passion. "One-eyed Jimmy has gone to the Land of Israel," he reported to Dov Hoz, referring to James de Rothschild, the son of Baron Edmond, who eventually paid for the construction of the Knesset building; he had lost one of his eyes in a golf game.

Shertok: "Jimmy has kingly pretensions ... He is driven by leadership aspirations, overweening ambition and power, envy of Weizmann on the one hand and envy of Jabotinsky on the other, and he thinks they are both heroes in the eyes of well-known circles and wants to snatch the imaginary laurels from their heads." He described Rothschild as a "degenerate nobleman" and "a maniac in the colloquial sense." There is no need to elucidate how dangerous he is, noted Shertok, or for that matter, his supporters. One is "a spy and an informer," another is "a poor, naked, stupid baby" and the rest are "infernal." Shertok instructed Hoz on how to deal with Rothschild: "Extract as much money as possible - and commit to absolutely nothing."

Total self-effacement

He often used hyperbole, perhaps in the style of the times. When his raincoat was stolen, he reported that he had suffered "a disaster." Like the diaries of prime minister Moshe Sharett, the letters of the student Shertok reflect a boundless egocentricity alongside a tendency to total self- effacement when in the gigantic shadow of an admired leader. He traveled from London to Vienna, although in the context of his Zionist activity, but his sister Rivka who was living there did not take advantage of his presence to get married at long last. He felt that she was wasting his precious time and was deeply insulted. Insult, it seems, was also one important, fairly pathetic element, in his later life among the other characteristics of his identity. He always felt that he was not getting the respect that was due to him, he always felt denigrated and downtrodden: "Moshe the water-skin," he wrote of himself in one of the letters, always with utter seriousness, with no self-irony, almost without a smile. Almost everything is equally important and unimportant: the future of the people and the bathwater, his life's dreams and the woolen socks he needed.

The diary of prime minister Shertok reflects a painful and embarrassing self-abnegation toward David Ben-Gurion; the student Shertok abnegated himself before Berl Katznelson. "I think of you especially all the time and I submit myself to your judgment," he wrote to him, "to you who are so distant and so close to me, dear and beloved. You cannot know and you cannot imagine what you are to me. I am afraid to tell you this openly and outright. I am doing this also to obligate you to responsibility, responsibility for myself. To not forsake me and do not grow distant from me. I need you like air to breathe, like light for my eyes."

In one of his letters to his sister Rivka he wrote: "Sometimes I regret that I am not a woman."

The letters to Rivka were written as if to a lover. However, to Zippora, his future wife, he wrote as if to his sister or to his mother, and she was, he said, "so very, very distant, misted in clouds of distance and time."

His Hebrew is admirable and his letters are a testament not only to an elite that has lost much of its influence, but also to a literary medium that electronic mail has almost rendered extinct. Tamar Gidron, Yaakov Sharett and Rena Sharett have edited these letters very intelligently, with useful notes, appendixes and a praiseworthy index.

|

|

Moshe Shertok (later Sharett) with his sister Rivka, 1917. |

|

|

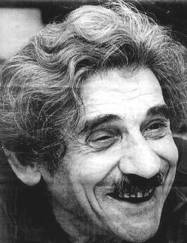

Yehuda

Sharett

Yehuda

Sharett

From the net: · Israel Kibbutz Choir

The choir

comprises around fifty members from kibbutzim around the country. It was

founded in 1955 by Israeli composer Yehuda

Sharett. They meet

weekly in Tel Aviv for rehearsals and specialize in Israeli and Jewish music.

They have recorded Israeli compositions.

…..pioneer-composer Yehuda Sharett, whom I once met; he was carrying a

backpack filled with books. He told me: “When I was twenty, they put me in

charge of getting books by post to the mobile library for the workers in the

Jezereel Valley. I would carry them heavy piles of books before they set out on

their roaming to the tent camps that went from one place to another in the

valley. People would ask me, ‘Yehuda,

why are you carrying all those books on your back all alone?' And I would

respond, ‘I like the idea that the spirit has weight!'”

…the theme of the last movement is the song “Rachel,” by Yehuda Sharett, from the poem of

the same name by a Jewish émigrée from Russia who named herself after the

Biblical Rachel. She came from a family used to luxury and she died in poverty

in Tel Aviv. She was left to live in a half-world between dream and reality

because of an unhappy love affair with [Zalman] Shazar, later the president of

Israel.

Yehuda Sharett's

melody developed from the musical impressions that he got in Israel in the

1930s and it became very popular among the Israeli settlers. Daughter of

Yehuda: Hilla Sharett

Hila Sharett

Hila Sharett

Kazablan, Hila Sharet

Kazablan, Hila Sharet  Work Type: photographs

Work Type: photographs  Creator: Haramati, Israel (n.d.),

Israel

Creator: Haramati, Israel (n.d.),

Israel  Date: 1967

Date: 1967  Topics: plays

Topics: plays  Nationality/Culture: Israel

Nationality/Culture: Israel

|

|

Tsivi Sharett wrote;

…My granfather Yehuda Sharett was a Choral Conductor, Violinist Composer and Educator. I remember how he was talking to me about practising and these special relationships we have with our instruments..I remember playing with him the first movement of Bach Violin Concerto in A minor and him trying to teach me Harmony.