picture1

Also known as; Vilna (Hebrew, Latin, English until 1945, Italian, Spanish, Slovene, Finnish, old Romanian variant) "The Jerusalem of Lithuania" (East European Jewry), Vilne (Yiddish) Wilno (Polish), Wilna (Dutch, German), Vilnius (Lithuanian, English, French, Norwegian, Portuguese, Romanian, Swedish, Turkish) Vil'njus (Russian, Ukrainian) Vilnia - (Belarusian)

From 1323 to 1794; capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

1794 – 1914 (Pre First World War); Russian Empire.

1920- 1939; Poland

1944- 1990; Soviet Union

Since 1990; the capital of Lithuania

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Taken from “ Jews of Lita”

By Israel Kloizner, Ph.D.

Translated from Hebrew by Eilat Gordin Levitan

Table of content;

Establishment of the Town

Struggles With Local Population

Census of the Year 1645

The Rulings of the 1650s

Continuing Struggle with Local Residents

Jerusalem of Lita (Lithuania)

Under the Russian Rule, 1794-1914

Some Jewish Statistics

Jews in Commerce and Industry

A Cultural Center for the Jews of Eastern Europe

The First World War in Vilna ( 1915- 1918)

Times of Transition to Polish rule ( 1918- 1920)

Under the Polish Rule (1920- 1939)

Under the Lithuanian Rule (October, 1939- June 1940) and Soviet Rule (June 1940- June 1941)

Natives of Vilna;

Rabbis and Torah Personalities

Other Well-Known Jewish Citizens of Vilna

Vilna’ war refugees; 1939 – 1940

----------------------------------------------

Establishment of the Town

The town of Vilna (in Lithuanian, Vilnius, and occasionally also known as Wilna) was founded at the beginning of the 14th century, approximately in the year 1320. Very rapidly, it became a central town in Lithuania, both as its strategic and commercial headquarters. The municipal officers relocated here, and in 1387, the Grand Prince Jogaila gave Vilna autonomy, similar to the autonomy of Magdeburg. According to this bill of rights, the local population had a right to commerce, handcrafts, and positions in the local municipality. Only town residents, however, were granted these rights.

By the end of the 14th century, three central Jewish communities existed in broader Lithuania. These were located in the towns of Grodno, Brisk and Trakai. Vilna, however, was nigh on impossible for the Jews to settle in, because only the original residents had rights to commerce and work there. Nevertheless, some Jews came as guest merchants as well as to work in the public municipality.

Beginning of the Jewish Community

It is said that the old cemetery in Vilna was built in 1487, although there is no written proof of such. In the year 1527, the local Christian population of Vilna received exclusive rights from the old King Sigmund; according to these papers the Jews were not allowed to be merchants or to live in the region. We may assume from these documents that law was passed after the Jews began settling in Vilna to engage in commerce. The Jews, however, could not let go of such an important administrative and commercial center and kept looking for some inconsistency in the special rights that Christian residents received. Slowly they were able to find such ‘cracks’ in the document and settled legally in the town.

The Lithuanian prince Jogaila (at this point also the King of Poland) needed the assistance of certain Jews who were very well-off and knowledgeable in particular fields; in return for their assistance he bestowed upon them rights to manage the mint in Vilna and collect taxes. These Jews lived in Wilna legally. In the year 1551, King Sigmund August I of Poland (succeeding King Jogaila) permitted two Jews from Krakow to become merchants in Vilna; he gave similar rights to his Jewish assistants. These Jews were allowed to rent homes, own stores and warehouses, and to barter goods. Such special rights began breaking the rigidity of the old codex from the year 1527, which had banned all Jews from such endeavors. In addition, the gentile nobility helped the Jews in their quest to reverse the old restrictive settlement laws. The Lithuanian Council (Seimas) gave, in the year 1551, special exemption from taxes to Jewish assistants to King Sigmund owning houses in Vilna.

Many Jews began to reside in these houses owned by the noblemen, working in stores and other commercial endeavors for the Grand Prince. It is thought that they built the first synagogue in Vilna around 1553. Increasingly more Jews moved here, forming a community that economically threatened the gentile population, who feared commercial competition from the Jews.

In the year 1592, some of the local Christians staged a small pogrom, destroying the synagogue, stalls, and apartments of the Jews in a street already then named Jewish Street. Using this pogrom as example of Christian hostility, the Jews convinced the King to give them complete legal rights to settle in Vilna. A year later (in 1593), the Jews received from Sigmund III, in a special bill of rights, a permit to live in Vilna. They were granted residence in the homes of the nobility, freedom to practice their religion, and permission to engage in commerce. After some time, Jews also received permission to establish public institutions for their community, such as a cemetery, a bathhouse, and a slaughterhouse. It is only at this point that the Jewish community came to be recognized as fully legal in Vilna.

picture 2 ( same as 1- cut another way)

Struggles With Local Population

This original bill of rights did not solve all the obstacles that the Jews of Vilna faced in regard to commerce and work. There was nothing in the bill in regard to handicrafts. The Christian population insisted on exclusivity in such work and fought any gap in their monopoly, using even violence and physical force against those Jews who tried to engage in handicrafts. The heads of the Jewish community of Vilna tried to appeal to the King for greater rights; simultaneously, they also asked for assistance from the nobility in receiving such rights. The Jews could easily have been more successful in business and in establishing themselves given the condition of free competition, but they were permitted to have only meager earnings at the time. It was in the interest of the nobility, who wanted to receive cheaper merchandise, to weaken the powerful Christian merchants and aid the ambitious Jewish workers.

Thus, in the year 1633, the heads of the Jewish community received a basic bill of rights from King Vladislav IV. The king not only reinstated the rights they had received earlier, but also allowed the Jews to own stores, open craft-stores, and to engage in liquor, leather-goods, and fur manufacturing. Furthermore, they were permitted to purchase and raise livestock in Vilna. This bill of rights contains the first mention of establishment of a small living area for the Jews. The creation of a ghetto was a new concept, designed to protect the Jews and aid them in the case of a pogrom. However, the Jews did not want to be contained in a small area. In the original bill, they were given 15 years to establish a ghetto, but they extended this date continuously.

During these years, a few of the most important Jews of Vilna succeeded in establishing a certain freedom of commerce for themselves in Lithuania. The king granted such a bill according to the wish of the nobility. The new bill ran as follows:

(1) Jews are allowed to open 12 stores whose fronts open onto Jewish Street. In these stores, the Jews are allowed to sell various merchandise. This right is valid for ten years. Certain merchandise will be limited. For example, liquor is only permitted to be sold to the Christians in mass quantity (not for individual sale).

(2) Jews are permitted to have professions only where there is no Christian competition. In other crafts, they are only allowed to pursue the craft to satisfy their own needs.

(3) The area designated as the ghetto, will be enlarged. Jews need pay no tax to the local municipality but are required to pay state tax. In addition, they must pay a yearly sum of 300 Zloty, which, during wartime, is increased to 500 Zloty.

The local gentile population greatly opposed this bill, and in the year 1634 (and again in 1635) they carried out pogroms against the Jews, destroying the Jewish cemetery and the synagogue. The investigative committee appointed by the king to examine the details of these pogroms did not succeed in finding the locals guilty of these crimes. They reported that the pogroms were carried out by anonymous vandals, and appointed the local municipality responsible for defending the Jews. In consequence of the pogroms, the Jews were allowed to construct gates guarding the streets they settled in. To compensate the Jews for their losses, the municipality permitted them to sell liquor in twenty homes instead of the previous twelve. The yearly taxes to the municipality, however, were increased to six hundred Zloty. Once again, Jews were permitted to operate their stores for ten upcoming years. Before much time passed, the Jews were able without much tribulation to receive an extension on this store ownership, in spite of the bitter opposition of the local Christian population.

Census of the Year 1645

In 1645, the town of Vilna published statistics about local Jews. The leaders of the community walked through the ghetto and several neighboring streets, registering each house containing Jewish residents and those houses that were for sale. This highly imprecise census found that there were 262 Jewish families living in the ghetto. If we estimate that each family was composed of five people, we may assume that there were 1310 Jews living in Vilna at the time. Since most of the Jews lived in the concentrated area aforementioned, the census did not take into account those living under the fortress (in Lithuanian, vyskupija). Taking this into consideration, we may more accurately estimate that there were in reality around 3000 Jews living in Vilna at the time of the census. In contrast, there were around 12000 Christians living here at the time.

The Rulings of the 1650s

Originally, the rulings of the 1650s did not affect the Jewish community of Vilna directly. Eventually, however, the changed conditions that affected the Jews of southern and eastern Poland began to affect the economic situation of Jews in Vilna as well. The Jewish refugees that came now to work in Vilna increased the number of people competing for work. The original Jewish loaners of money now became needy of money themselves. The heads of the Vilna Jewish community borrowed large sums of money from Jesuit priests, giving them rights to their homes and membership to their synagogue.

In 1655, troubles overcame Vilna. The Muscovite army invaded the town and most of the community fled, traveling to Zamut and from there to Prussia. On the border of Prussia, the refugees encountered the Swedish army that had invaded Poland. While the Swedish army demanded certain levies, the Russian army that had invaded Vilna killed many of the Jews and burned the town. The fire lasted seventeen days, and the Jewish quarter was burned to the ground. Destruction of the community lasted until the Polish army liberated the town in 1661. The local Jews then returned to the area and began to recreate their community.

Picture 3.

Continuing Struggle with Local Residents

The reestablished Jewish community of Vilna was very poor and needed much assistance. The kings of Poland helped these Jews by giving them license to rent apartments in all areas of the town and to sell tax-deductible liquor. They also extended the Jews’ loans, decreasing the amount of interest owed. In addition, they gave Jews more permits to own stores opening onto non-Jewish streets. The local Christian population, however, once again fought against this assistance of the Jews, wishing to rid themselves of any professional competition from the Jewish merchants and craftsmen. They continued to file complaints regarding the Jews to the judicial system, sometimes taking the law into their own hands by molesting and hindering Jews. Still, a compromise had to be reached, and the Christians granted the Jews a limited amount of rights.

This trade conflict was exacerbated after the establishment of Christian trade unions that placed very strict limitations on Jewish tradesmen. After Jews complained to King Michael Wisniowiecki, he issued an order wherein it was restated that, according to the ruling of 1633, Jews were permitted to engage in all trades and crafts that were not under Christian monopoly that year. Such crafts included fur-trading, embroidery, and glass-blowing. The Christian trade union reached a compromise with Jewish tradesmen by limiting the numbers of Jews allowed into particular professions and by exacting dues from those practicing certain professions. In consequence, the Jewish tradesmen organized their own societies to protect their business interests. According to the ruling, Jews were allowed to enter only one Christian trade union – that of the barbers.

Despite this skewed compromise, occasionally the local Christians would organize assaults on the Jews of Jewish Street. The various Polish kings, however, attempted to defend the Jews. Such assaults mainly caused destruction of personal property, although a few Jews were killed in these incidents.

During the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the

18th, the Vilna area experienced many hardships: wars, starvation, fires, and

epidemics. During the Great Northern War (1700-1721), both the Swedish and

Russians entered Vilna, exacting fines and demanding taxes of the residents.

The Jews, too, had to pay large sums of money to the incoming armies during the

years of 1702 to1706. In result of the war, the years between 1708 and 1710 saw

starvation in the area, culminating in1710 with an epidemic killing many in the

town, amongst them Jews. Many large fires followed, some of them spreading in

the Jewish quarter. Fires in the years 1737, 1748, and 1749 leveled the

synagogue and Jewish public institutions.

Picture 4

Despite the difficulties of the Jews and others at this time, the Christian population never stopped fighting for exclusive rights. In the year 1713, many trials were held incriminating the Jews. The leaders of the Jewish community, however, prevented the resulting judgments and sentences from being carried out.

In the year 1738, King August III issued the Jews a new bill of rights for the coming twenty years, allowing them to once again own stores and sell hard liquor. Once more, the Christian population fought these rights bitterly. The municipal authority sued the Jewish community in the court of the king, the primary complaint being that the Jews had deceived the king. These gentiles tried to reestablish the rules discriminating the Jews that had been set forth over a 100 years previously and in 1740 they received a judgment in their favor. This judgment was based on that of 1527. Accordingly, the Jews were no longer permitted to reside in Vilna. Many left the town before the end of the trial, contributing to the biased nature of the verdict.

Thus, the Jews of Vilna faced exile yet again. The Christians attempted to evict the Jewish merchants and craftsmen from the town. However, the minister of the region came to the help of the Jews, establishing a committee to examine both sides of the issue and reach a compromise. A long and tortuous debate began. The side of the Christian townspeople prevailed, and the Jewish community saw no choice but to sign a compromise that was very biased. This compromise delayed the ruling of 1740 (stating that Jews must leave the town because they had deceived the king) but did not fully abolish it.

In light of the compromise, the entire Jewish community became responsible for each Jew who disobeyed its rulings. In this way, the contract ultimately became very helpful to Jewish commerce. Nevertheless, Jewish tradesmen ignored the ruling at the time it was issued, opening large stores with fronts that faced non-Jewish streets. They continued selling what they wished and taking part in whatever crafts they specialized in, and even going so far as to enlarge the area of the prescribed Jewish settlement. When the municipality realized that the Jews were not acting according to agreement, they renewed the battle against them. The Jews began defending their position, fearing exile. Their strategy was offensive, and in the year 1756 the judicial code of the king decreed that the contract from the years 1742 was valid. In a sense, the Jews had prevailed, although they were very limited by this contract.

In the year 1783, the trade unions and leaders of the Jewish community arrived at the courthouse of the king. Among the heads of the community, Arie Leib Myetes’ was very efficient at this task, finding an ally in the assistant to the counselor, Joachim Harptovic, a very educated and enlightened man. Working with him, the ultimate judgment was made in the spirit of progress and liberation. It established new rules concerning the ghetto, stating that Jews need not live in a limited area of the town, as their number had greatly increased and the three narrow streets designated to house them a hundred and fifty years ago were no longer sufficient (these streets still remain under the names of Zhydu, Sv. Mykolo, and Mesiniu Gtv.). Now they were allowed to reside in all areas of the town with the exception of two streets (from the gate of Ostrabrama to the Christian cathedral and from the Trakai gate to the St. John Church). Even in these two streets, Jews already living in houses were permitted to remain. Also included in this ruling was the pronouncement that Jews living in these streets must contribute to the beautification of the town.

New edicts concerning taxes declared that Jews’ taxes would equal those of all other citizens, and the yearly tax of 600 Zloty was abolished. The ruling also established the freedom of Jews to participate in all commerce and craftsmanship, explaining that the contract of 1742 was a product of its time and its conditions could and would no longer be sustained. The ruling of 1783 also clarified that each person wishing to receive a license for craftsmanship would be tested by a committee that would be composed of both Jews and gentiles and would be appointed by the municipality.

This judgment was regarded as a big victory by the Jews of Vilna. In commemoration of it, the gravestone of Arie Leib Myetes’ reads “it is he who saved the Jewish community in the year 1783 and averted disaster in town through his cleverness.” The bill of 1783 ended a long struggle for Jews’ right to live, work, and engage in commerce in Vilna. Jewish commerce and trade increased, and many unions of Christian workers were terminated. Ultimately, the ruling legalized something that was long in existing and removed the obstacle of free progress in commerce and craft by the Jews.

Jewish Censuses at the End of the 18th Century

In order to determine accurate taxation, censuses were carried out in Vilna in the years 1765 and 1784. After Vilna was conquered by Russia, there were yet other censuses in the years 1795 and 1800. While these censuses are not accurate, we may still learn much from them. The most exact censuses were taken in 1765 and 1800. According to the census of 1765, the Jewish community of Vilna and its suburbs was compromised of 3887 individuals. In the year 1800, 6971 individuals inhabited the same area. The total number of residents at the end of 18th century, including the Jews, was 17351 individuals. Thus, the Jews composed almost half of the total population at the time.

Internal Jewish Politics During the Years of the Polish-Lithuanian Kingdom

The Jews had become autonomous and their leaders served in a committee, chosen by the community to represent them in the larger population and negotiate with the local government. They collected taxes, had formed their own judicial system, were responsible for the health and sanitary conditions of the Jewish quarter, and supervised Jewish education. Each year, new community, judicial, and religious leaders were elected by the community. In certain job areas, such as education and health, special societies existed (Talmud-Torah for education, Bikur-Holim for Health Care, and CHK). Each such society elected its own leaders.

The Vilna Jewish community began to take part in the Committee of the State of Lithuania for the first time in 1652. In time, it became very prominent in this committee, since the Jewish quarter had became a significant metropolitan area of the town. Taking example from the Christian craftsmen, the Jews also organized trade unions. At the head of the society of weavers was CH. K. Schmuckler. The number and size of such societies increased steadily. Most such groups attempted to establish their own synagogues.

There existed a noted hierarchy among the leaders of the community. In order of importance, these leaders were: the rabbi, the av beit din (religious judge), the magid, the writer of official documents, the beadles, the legal community representative (shadlan), the doctor, and other community workers. It was the wealthy and the learned who influenced the community the most. Only well-to-do or learned individuals were elected as leaders of the committee and societies. Even in difficult times when the community required representatives reflecting their decrepit state, those elected were wealthy. They in turn elected their relatives for more minor judicial positions.

Originally, the community was ruled by volunteers who cared for the betterment of the public. Among them was Eliyahu Hasid, brother of Yisaschar Bar, son of Rabbi Moshe Kramer (av beit din of Vilna, died in 1688), and great-uncle of the ‘Genius of Vilna’ (1720-1797). Another like him was Yehuda S”od (son of Eliezer, died in 1763, was the father-in-law of Shmuel, son of Avigdor, av beit din of Vilna). Following this type of rule, the job fell to the hands of the wealthy, who wanted power and control. Consequently, a great debate started in the second half of the 18th century between the av beit din Shmuel, son of Avigdor, and the head of the community, Abah, son of Ze’ev Wolf. The Jewish craftsmen opposed the head of the community, and their representative demanded either the abolition of the leading committee or at least a limitation of duties to religious and charity work. Both sides, for the first time, appealed to the government. The autonomy of the Jews, however, was greatly hurt by appealing to outside help in settling a local debate.

Jerusalem of Lita (Lithuania)

picture 5

As the Jewish community became more established in the first half of the 17th century, Vilna became the center of the Torah. Many religious learned Jews from other places, such as Bohemia, Austria, Germany and Poland arrived here. Moshe Rivkas’, son of the writer and scribe of the Jewish community of Prague, brought with him to Vilna the library that had belonged to his father, collecting many new works as well. Many at the head of the religious community were well-known, amongst them famous rabbis such as Moshe Lima (son of Yitzhak Yehuda, died in 1670) who wrote the book “Chelkat Mechokek” that became renown throughout the Diaspora. The religious judges in Vilna at this point were Ephraim (1616-1678, son of Yaakov The Cohen, “Shar Efraim”), Shabtai Cohen (son of Meir The Cohen, 1622-1663) Aaron Shmuel Keidanov (known as the Ma”hrshk, 1614-1676, born in Kedainiai), and Hillel (wrote Beit Hillel, born in Galicia, religious judge in Vilna). Due to the destruction of the community in 1655, many of these learned men fled and settled in the west. Some of them received jobs as rabbis in important Jewish communities. Rabbi Shah Shabtai Cohen became the rabbi of Holesov in Moravia. Ephraim, writer of “Schar Efraim” also became a rabbi in Moravia; Aaron Shmuel Keidanov became rabbi of Pielt in Germany; Hillel became rabbi in Altuna, Hamburg. Eventually, rabbi Moshe Rivkas’ (son of Tzvi Naftali, died in 1671) returned to Vilna from Amsterdam, where he wrote the book “Be’er Hageola”.

Slowly, the community returned to its prominent cultural and

religious position, and in the 18th century Vilna again became filled with

Jewish writers and learned men: Yaakov Amdan wrote a book about the learned men

of Vilna during that time (Megilat Sefer: “Better known and more glorious than

all Polish people, they were the most devout learned men and did not leave the

house of prayer and learning and would instead sit there day and night with

their books They became a den of lions of the Torah, all of them received

positions of the teachers of Israel”)

Picture 6

Special among these learned men and writers was Eliyahu Hasid Ben Solomon, who became better known as the Genius of Vilna (1720-1797). He strengthened traditional Jewish values, keeping them insulated from the new movement that was taking form in the Jewish streets. Nevertheless, the upcoming movements took root, examples being the Hasidic movement, established by Baal Shem Tov, and the enlightenment movement that came from Berlin under the influence of Mendelssohn (the grandfather of Mendelssohn the musician). Only a small number of the heads of the Vilna community of the learned were affected by the Hasidic movement. This is due to the work of Rabbi Eliyahu, who stubbornly resisted it.

Already the first of these enlightened Jews of Vilna worked to preserve the Hebrew language. Taking great interest in its grammar, they were also curious about modern additions to the religious text. They continued its tradition, preferring it over philosophy. Vilna, with its rabbis, writers, philosophers, and educated people, became renowned as the center of spiritual life of the Jews of Lithuania. Thus, it was rightfully named the ‘Jerusalem of Lithuania’ (Yerusholayim de-Lita).

picture 7

Under the Russian Rule, 1794-1914

In 1794, around thirty Jews were killed in a Vilna suburb by the incoming army of the Russian empire. In 1812, the French army conquered the town and the Jewish population suffered greatly. The old cemetery became a pasture for cows and sheep. The Jews helped the Russian army to fight the French, hoping Czar Alexander the First would improve their situation. This was a misconception, as the situation during the rule of the brother of Czar Alexander Nikolai the First was very bitter. A draft claimed young Jewish children for the army, causing great alarm in the community. Despite many of Jews’ pleas, this order was not revoked and greatly hurt the population, resulting in internal struggle in the community because it was the leader of the community who were responsible for fulfilling the specifications of the draft. The governing committee secretly kidnapped impoverished Jewish children to fulfill the requirement of the draft, causing the population, especially those who were poverty-stricken, to revile the leaders of the community.

In 1802, an order came to the Russian-occupied Vilna stating that a certain number of Jewish representatives must be chosen for the municipalities, as was custom in the Russian empire. The chief of the central municipality greatly objected to the members of the Jewish leading committee. Thus, after pleas of the Jews to revoke this order, it was cancelled by the municipality. The subject was again brought to light in 1816. The mayor of the Vilna region suggested that some Jews assume positions as representatives in the municipality, and so in 1817, two Jews were chosen for this general committee. Seven of the gentile members of the committee announced that they would not take part in any organization that contained Jews. The gentiles were put to trial for refusing to work with the Jews, although the outcome is not known.

The Jews remained in the general committee until the year 1820, when the Russian leadership acquiesced to the pleas of the gentiles in forbidding the Jews to take part in the committee. Once again, this issue was debated for a long time – until the year 1836 – when it was finally decided that Jews would no longer be allowed to participate in the committee of Vilna. Although this decision was an exception amongst the rules applying elsewhere, during the entire period of Russian control of Vilna, Jews were not members of the leading committee. It was only according to the Law of 1892 that a few Jews were permitted to join the committee, although even then they were not allowed to take active part in its decision-making and work.

In 1844, Russian rulers annulled the autonomy of the Jews over their affairs. The beadles of the synagogues became the caretakers of the social and religious life of the community. The beadle of the largest synagogue became the head of the community. By the 1840s, the situation of the Jews under Russian rule had become very difficult, and in 1846 a renowned Jew by the name of Moshe Montefiori (1784-1855) came from the West to plead with the Czar to revoke a new ruling hindering the Jews. During his visit to Russia, Moshe stopped in Vilna, where he was received as an honored guest by the local Jews. He investigated the situation of the community and received detailed written reports from educated Jews living here. Despite Moshe’s pleas, however, the Czar did not revoke the ruling.

In the year 1850, yet another ruling came from the Czar, this time in regards to the costume of religious Jews. Now, Jews were forbidden to wear long gowns such as those of Polish Jews. In addition, rulings regarding traditional men’s sideburns and women’s wigs were issued. Most in the Jewish population strongly objected to the ruling, although they eventually became accustomed to the new fashion.

Following the demise of this evil Czar there was improvement in Jews’ life in two areas: that of army service and of permission for Jews to breach the Pale of Settlement. In the year 1861, the rule decreeing that two streets of Vilna must remain unpopulated by Jews was eliminated. However, a Jewish resident of Minsk by the name of Jacob Barfmann converted to Christianity, causing great damage to the Jewish population. In the year 1866, he arrived in Vilna and published an article suggesting that Jews were a nation within a nation. This article caused great turmoil amongst the Vilna ruling class. Mr. Barfmann was asked to collect testimony from books of the Jewish community showing the ‘true nature’ of the Jews. This appointment caused great turbulence amongst the Jewish population, and the general governor agreed to the suggestion of a Jewish publisher from Vilna, Yaakov Barit, founding a committee of educated Jews who would investigate the claims made by Mr. Barfman. This committee existed until 1869. Despite the fact that Yaakov Barit was successful in proving to the members of the committee that the claims that Barfman made were false, Barfman continued in his activities and published, with the help of gentile authorities, a book about the Jewish community. This propagandist and fallacious book insinuates that according to faulty interpretation, the books of the Jewish community are erroneous in regards to the true nature of the Jews. Barfmann’s book was sent to many government officials and was used by its clerks as an official document describing the Jewish community and their relation to the state.

During the reactionary period when Czar Alexander III came to power, Jewish Vilna was very involved in a movement for equal rights and national liberation. In 1872, Vilna established the first Jewish Social Center in the world. In addition, one of the first Zionist Unions, Hovevei Zion (From its inception, the Hovevei Zion groups in Russia sought to erect a countrywide legally recognized network. After negotiations, in which the authorities demanded that the society be set up as a charitable body, its establishment was approved, early in 1890, as ‘The Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Eretz-Israel,’ which came to be known as ‘The Odessa Committee.’), was established here in 1882. In the year 1897, a meeting was held for the entire committee of the Social Democratic Jewish Party (the anti-Zionist Bund – “Like other Jewish Marxists, the Bund argued that, rather than emigrating to Palestine, Jews should combat racism wherever they were. So it was extremely hostile to Zionism, which it saw as a refusal to fight anti-Semitism – and indeed a concession to it.”

Taken from http://www.sa.org.au/cgi-bin/index.cgi?action=displayarticle&id=214).

picture 8

Young

Bundists in Vilna. The original caption reads, "taken before Leike Zafron

went away." Among those pictured is Etta (Miransky) Michtom (second row

from the top, third from the right)

.

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, this party became very active in Vilna.

In 1902, a young Jewish shoemaker by the name of Hirsch

Leckert (1879-1902) attempted to assassinate the Vilna governor, von Wahl, who

had been very cruel to protesters on May 1st. The governor was wounded, and

Hirsch Leckert was hung. During the same year, the religious Zionist

organization held a meeting in Vilna. The city became a center for the laborers

of Zion. In 1903, Doctor Herzl, president of the Zionist movement, stopped in

Vilna on his way to St. Petersburg. This visit resulted in a great

demonstration of Vilna Jews in support of Herzl and his doctrine. Between the

years 1905 and 1910, Vilna was the location of the Zionist Committee of Russia.

In 1906 Vilna witnessed a meeting of the Union for Equal Rights of Russian

Jews; Doctor Shmaryahu Levin was elected as a representative to the Russian

Duma. At this point, he lived in Vilna.

Picture 9. Delegates to a congress of the Tse'irei Zion movement, Vilnius 1921. Shlomo Farber (front row, second from the right); Menachem Rudnicki - Adir (front row, fourth from the right); Chaim - Shalom Kopilowicz (front row, third from the left); Avraham Solowiejczyk (front row, on the left); Lewin (standing, second from the right; first name unknown), a delegate from Molodechno; Israel Shafir (standing, third from the right); Nachum Kantorowic (standing, fourth from the right); Israel Marminski - Marom (standing, fifth from the right); and Margolis (standing, fourth from the left; first name unknown), a delegate from Svencionys. Also in the photo, seated: A. Katz, Shraga Antovil, Reuven Boniak, Shlomo - Yitzhak Alper, Eliahu Rodnicki, Nechama Horwic, Yitzhak Walk, Chaim Fejgin, and Yitzhak Schweiger, a Zionist emissary from Mandatory Palestine.

Some Jewish Statistics

The number of Jews in Vilna steadily increased during the 19th century. By 1832, Jews constituted the majority of the town population. While Vilna housed 20706 Jews, it was the residence of only 15200 gentiles. According to the census of 1897, of 154532 Vilna inhabitants, 63997 were Jewish; Jews made up 40.9% of the population. In 1916, Vilna’s inhabitants had decreased to 148840, yet amongst them were 61263 Jews, or 43.5% of the general population.

picture 10

Jews in Commerce and Industry

Vilna soon became a center of commerce and industry. The town’s merchants shipped products to distant markets all over the Russian Empire. Vilna also became a transit station for the merchandise traveling between Russia and Germany. The local manufacturers, specialists in their professions for generations, developed contemporary products, such as mass-produced ready-made clothing and gloves. In the surrounding neighborhood of Vilna, they also generated wood products, using mills and factories to make furniture. Vilna residents controlled flour mills, beer and tobacco factories, sweet and sugar factories, and printing presses as well as tanneries. Jews took increasingly large part in such commerce in the 19th century. In 1806, only 22.2% of merchants were Jewish. By the year 1827, Jews made up 75.6% of merchants: almost the entire commerce in Vilna had passed to Jewish hands. By 1875, of 3195 merchants, 2752 were Jews, or about 86%. In 1897, 77.1% of merchants were Jewish.

Particularly large was the number of Jews who owned small stores and businesses. According to the census of 1897, the professional classification of Jews of Vilna was as follows: merchants – 6117 individuals; industry and manufacturing – 13573; transportation – 875; agriculture – 78;doctors, lawyers, and the like – 1026; others – 6926. Accordingly, most Jewish residents of Vilna were involved in industry and production. These small-time Jewish manufacturers began exporting their goods - ready made clothing and gloves - to all areas of Russia.

In 1914, according to a census carried out by Jacob Laszcinski, more than 50 manufacturing enterprises belonged to Jews; in each one of them worked more than ten people. In some of these, there were twenty and in others as many as forty laborers. Small manufacturers yet abounded. That year, of 131 Jewish glove-makers, 78 employed 308 laborers and 125 assistants. Other than these laborers, between 250 and 300 workers, mostly women, carried out small assembling jobs from home.

In the sowing industry of 1914, about 1000 Jewish enterprises existed, collectively hiring around 2000 laborers. Ready-made clothes were sent to Caucasus, Siberia, and central Russia. Vilna’s main competitor in the clothing trade was Poland. These sowing assemblies operated very similarly to US enterprises, with detailed division of labor. 200 ready-made clothes manufacturers hired between 500 and 600 laborers; some establishments employed 30 or 40 laborers alone. Of around 100 shoe-makers, only three were gentile. Collectively, 500 Jewish workers were employed in the shoe-making industry. Three to four thousand additional laborers made socks; many worked from home. Other professions – such as those of hatters and saddlers – were a Jewish monopoly.

In 1815, the first Jewish factory was opened for the production of simple cloth. By 1858, almost all factories were owned by Jews. Although they were not large, the 43 factories employed 210 laborers. During the years from 1870 to 1880, this industry was much encouraged by authorities. In 1887, 53 of Vilna‘s factories were operated by Jews; together they used the services of 1469 manual workers. Although ten years later the number of Jewish factories had decreased to 49, they now employed 2378 laborers. Just before World War I, the number of Jewish factories increased to 125 and the number of laborers to 4671. Other than the fields already mentioned, there were no truly developed industries in Vilna.

As Vilna was a center of commerce, sectors of important banks were opened here. Jewish merchants and tradesmen opened their first savings and loan bank in 1904. The previous year, in 1903, Doctor Benjamin Pin, the son of Räshi Pin, left in his will some money to assist in manufacturing and subsequently became very important to the industry. His example was followed by similar benefactors in other Russian towns.

picture 11

A Cultural Center for the Jews of Eastern Europe

Vilna continued to flourish as an eminent cultural center throughout the 19th century. It was the center of the Torah; the Enlightenment spread through the town and its environs. While many distinguished writers and progressive thinkers were raised in Vilna, others came from different towns. In the middle of the 19th century, it became a hub of Hebrew literature.

A central personality amongst the free-thinking inhabitants of Vilna was the writer Mordechai Aaron Ginsburg (1795-1846, born in Salant);

among poets who originated in Vilna we must mention

Avraham Dov Hakoyin Levinsohn (born in Vilna in 1794, died in 1878) and his son Micha Yosef Levinsohn (1828-1852) as well as

Schlomo Zalkind (died in Vilna in 1868) and

Yahudah Leib Gordon (born in Vilna in 1830, died in St. Petersburg in 1892). Vilna also housed researchers the likes of Matityahu Strassen (son of Shmuel, born 1818 in Vilna, student of teachers from Lebadova and Ilya, died in 1886 in Vilna),

Yitzhak Isaac, son of Yaakov,

Avraham Zagheim (died in Vilna 1872, son of Yosef),

Smuel Yosef Pin (born in Grodno 1819, died in Vilna in 1890),

Eliezer Lipman Horowitz (born in Vilna in 1815, died 1852),

Juhoshua Steinberg (born in Vilna in 1839, died in 1908). Also there were welknown writers like Kelman Schulman (born in 1821, died in 1899 in Vilna),

Benjamin Mendelstamm (born in 1800 in Jagar, died in 1886 in Simpropol),

Isaac Meir Dik (born in Vilna in 1807, died in 1893),

Moshe Reicherson (born in Vilna in 1827, died in 1903),

David Moshe Mitzkohn (born in 1836, died in Vilna in 1887),

AY Papirna.

The well-known writer Mapo (born in Slabodka in 1908, died in Konigsberg in 1867) belongs very much with the Vilna literary spirit. These scholars wrote in Hebrew, the literary language of the Jews of Eastern Europe. Eventually, the Yiddish language, the vernacular among Jews, also became a literary language, furthered by writers such as A.M. Dik and Michail Gordon. The common sharp humor of the times was expressed by the national comedians Motke Habad and Sheike Feifel, the flute-player. Members of a well-to-do enlightened class, such as Eliezer, Nisan, and Moshe Rosenthal, Mordechai Nathanson, Elazar Halberstamm, and others, also lived in Vilna at the time. What is particularly evident amongst these writers is their deep-rooted love for the Hebrew language as well as for the Bible and the land of Israel. In addition, they recognized the unity of the Jewish nation that had spread out during the Diaspora and had a deep love of traditional literature.

In the year 1799, two printing houses transferred from Poland to Vilna. Both had Hebrew divisions. In the publishing house of the Polish Zawadski, the head of the Hebrew department was Menachem Man, who changed his last name to Romm. In 1835, Romm began printing, in partnership with a few wealthy Vilna residents, the Bible. At the same time, the Bible was also printed in the Sloboda printing house. A fight ensued and was taken to court, where it was decided that the printing house of Romm would be the sole publisher of the Bible. In consequence of this verdict, the government closed all Hebrew printing presses in Russia with the exception of Romm’s in Vilna and another in Kiev. Romm now had a monopoly on almost all Hebrew literature of the region and became very successful. The Romm printing press was used by the writers of Vilna as a publishing house. In 1863, a new publishing house was opened by Rashi Pin and Rosenkrantz; following this, many other such houses were launched.

Several Jewish students studied in the Polish university in Vilna. In 1808, the university established a program for teachers of secular Jewish schools, but this program existed for only half a year. In 1830, Jewish academia established a secular school in Vilna, but, once again, this did not last long. In the year 1841, a group of educated Jews, headed by Nisan Rosenthal (died in 1816 Vilna, was born in Yasinovka),

established two schools at which children studied both secular and religious topics. In 1844, the government of Vilna opened a school for rabbis that in 1873 became a school for Jewish teachers. This establishment was largely intended to further Russification among Vilna Jews, providing general schooling rather than specifically educating rabbis and teachers. Many students of this establishment became known as writers and researchers. Among these were Dr. Yehuda Leib Kantor (born in Vilna in 1849, died in Riga in 1915),

Doctor S Mandelkern,

Aaron Shmuel Lieberman (born in 1845, committed suicide in 1880 in the US), Abraham Eliyahu Arahbi, son of Yaakov (born in Novohorodok in 1835, and died in 1919),

Kahn Avraham (born in 1860 in Podbraze, died in 1951 in New York), and

L Livender .

picture 12

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a Hebrew high school with a primary language of Russian was established. Under the headmaster PA Cohen, many subjects were taught in Hebrew. The Zionists, becoming more and more influential in the area, established a modern institution for religious studies, and new, modern ideas became more common in the secular Hebrew schools as well. In some, Hebrew began to be taught in a more natural way, often replacing the more common Yiddish. Several Zionist women established at this time a Hebrew school for girls by the name of Jahudija.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Vilna was the cultural center for many Hebrew writers. Between 1904 and 1915, a daily paper, Hazman (the Times), was published, whose writers included Ben Zion Katz (born in 1875, died in Tel Aviv in 1958), Israel Chaim Tvajov (born in Druja in 1858, died in Riga in 1920), Yosef Eliyahu Trivesh (born in Vilna 1855, died in 1940), Shaul Chernovitz, YD Berkowitz (Ben Zion Yahuda?), Ben Eliezer (nee Moshe Galumbatsky, born in 1882, died in Tel Aviv in 1944), Y. Brashdeski, Hillel Zeitlin, and SL Zitron. Furthermore, a monthly newspaper was published by Zev Yewitz, called Hamizrachi. The weekly of the Zionists, Zionist Congress, was published in Vilna and targeted a youthful demographic. In addition, weeklies like Life and Nature were published by Lavner and Comrade published by Eliyahu Halevi Levin. Yiddish newspapers also flourished. In 1906, the Zionists began publishing a scholarly weekly, named Das Jidische Volk. Its editor was Dr. Yosef Floria. Other political parties, such as the Bund, the Zionist Labor Party, and the Socialists (SS) also published newspapers and books, mostly in Yiddish. The monthly Yiddish World transferred its location from St. Petersburg to Vilna, and was edited by S. Niger. A children’s Yiddish newspaper by the name of Grininka Biamelah was published by Hilperin Falak. Furthermore, an important scientific library was established in the town. Books were contributed per the inheritance of the learned Matityahu Strassen.

picture 13,

The First World War

The German army took over Vilna during Yom Kippur of 1915. A very difficult period came, a time of starvation and unemployment, followed by forced labor. The previously flourishing industry and commerce were eradicated. Although the town incurred a collective financial penalty of one million Marks, the Germans were not able to collect such a prodigious amount of money from the impoverished population.

During this difficult period, camaraderie flourished in the community. Helped with training of professionals and given employment opportunities, education in the Jewish community progressed and the first Hebrew-speaking high school in the Diaspora was established along with a Yiddish theater. At the end of the German rule, a democratic election of leaders for the Jewish community took place.

picture 14. A bicycle trip for members of Zionist youth organizations in Vilnius. The bicyclists, who set out on May 5, 1920 - the beginning of the Lag B'Omer holiday, carried a blue and white flag with the word "Zion" in Hebrew, and various placards, in Hebrew and Yiddish, with slogans in support of labor and the Jewish People's return to the Land of Israel

Times of Transition

At the end of 1918, the Germans retreated from the town. Local Polish citizens received leadership positions from the Germans, but a few days later, the Red Army invaded. Communist rule lasted for only a short time, but even in that time industry and commerce greatly suffered. The Communists took over many businesses and the situation of the Jews of Vilna became dire.

On April 19, 1919, the Polish legionnaires entered Vilna and began molesting Jews. However, the commander of the Polish army, Pilsudski (1867-1935), immediately announced that the duty of the army was to liberate the city and to give its citizens the opportunity to manage business as they saw fit. He instituted a democratic election and several Jews were elected to serve in the town council. On the 14th of July, 1920, the town once again was invaded by the Red Army. A day later, Lithuanians entered the town. At the end of that August, the Russians gave control of the town to Lithuanians, who promised the Jews national and cultural autonomy.

Under the Polish Rule

picture 15.

Soon thereafter, the Polish army, headed by general Zaligowsky, conquered the town. Under Polish control Vilna became a backwater Polish town without any commercial inflow. Its connection with the neighboring independent Lithuania was severed. The Jews of Vilna took part in the leadership of the town but were forced to fight for these rights. The duties of the Committee of the Jewish Community were decreased and, according to Polish diktat, became responsible only for religious and social work. Despite this, the Jews covertly conferred upon the committee greater responsibilities.

As the Vilna economy was stagnating, continuous emigration to the United States and other countries occurred. Nevertheless, Jewish schools, taught in both Hebrew and Yiddish, were established. In addition, schools training teachers in Hebrew and Yiddish and Hebrew and Yiddish high schools were opened. Polish authorities, desiring to educate Jews in Polish, opened a Polish public school for Jewish children. In addition, the Polish university in Vilna accepted only students with Polish high school diplomas. Thus, it became very difficult for any graduate of a Hebrew or Yiddish high school to be accepted. Notwithstanding this limitation, many Jewish students attended the university.

The main cultural loss for Vilna’s Jews was its position as the heart of Hebrew literature. The Jews who promoted Yiddish used this opportunity to open their own center and attempt to make Vilna the core of the Yiddish movement. They established several public high schools and a teaching seminary in Yiddish. They also tried to establish a scientific institute for high school graduates. This establishment was intended to carry out research on Yiddish language as well as Jewish history, statistics, and other such subjects. Known as the YIVO, it became famous throughout the Diaspora, but especially in Poland.

On Jewish Street, hostilities ensued between the Zionists and the Bund. While the Zionists controlled the Jewish community, the Bund strongly impacted its trade unions. During the few years prior to World War Two, Anti-Semitism spread all over Poland, including Vilna.

picture 16.

Under the Lithuanian and Soviet Rule

As soon as World War Two began, the Soviet Union occupied a large sector of Poland. Vilna was handed over to Lithuania by the Soviets in October 1939. Under the rule of democratic Lithuania, the situation of the Jews improved. Many Jewish refugees arrived from Poland to seek haven in Vilna. In June 1940, Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union. The Soviet rulers now began to deal with those who displeased them in Vilna: public leaders as well as writers and members of the Zionist party and other Jewish parties were sent to Siberia. Among those who were sent to Siberia, a few were executed. These were leaders of the Yiddish, Volkist, movements, among them Zalmand Reizin as well as the lawyer Yosef Chernikhov (also known as Danieli, was born in Slonim in 1882, perished in a Soviet prison in 1941.)

picture 17.

Natives of Vilna

Rabbis and Torah Personalities

-R’ Abraham Zvi, son of R’ Shmuel Isar Hacohen

- R’ Aaron from Vilkumir

- R’ Avraham son of R’ Eliyahu

- R’ Eliyahu son of Azriel

- R’ Moshe Simon Antokolski

- R’ Efraim son of Yakov Hacohen

- R ’Yakov Ashkenazi

- R’ Yitzhak Belser

- R’ Zelig Ruven Bengis

- R’ Bzalel, son Israel Moshe Hacohen

- R’ Israel Ginsburg

- R’ Nahum Grinhaus

- R’ Eliezer Eliyahu Dikes

- R’ Bzalel Dikes

- R’ Shaul Chaim

- R’ Halevi Horowitz

- R’ Avraham Zvi Halperin

- R’ Eliyahu Gershon Halperin

- R’ Yakov Zak

- R’ Israel Zakheim

- R’ Moshe Halevisaksh

- R’ Chaim, son of Shlomo Zalman

- R’ Hillel David Hacohen Traives

- R’ Yehuda, son of Eliezer

- R’ Joshua, son of Yosef

- R’ Chaim Uri Cohen

- R’ Yehoshua Heshil

- R’ Halevi Levin

- R’ Yehoshua Lang

- R’ Eliezer Landau

- R’ Yehezkel Halevi Landau

- R’ Yitzhak Eliyahu Landau

- R’ Yekutiel Zalman Landau

- R’ Alexander Moshe Lapidos

- R’ Noah Mindes

- R’ Hillel Milikovski

- R’ Menachem Eliezer, son of Levi

- R’ Moshe, son of Hillel

- R’ Moshe Ravkash

- R’ Yosef Skovic

- R’ Mordechai Eliezer Kovno

- R’ Zvi Hirsch Kedanove

- R’ Mordechai Klatshkau Melzer

- R’ Abraham Kretchmer

- R’ Shabtai, son of Meir Schah

- R’ Shlomo, son of Israel Moshe Hacohen

- R’ Arie Leib Shapiro

- R’ Yitzhak Eliezer Lipman Shershevski

- R’ Avraham David Strassen

-

Other Well-Known Jewish Citizens

-Alexander Ezra, actor

-Abraham Eisenberg, sculputrer

-Yeshayahu Eisenstadt, leader of the Bund

-Ben Zion Alpers, writer

-Lion Antokolski, artist and educator

-Mordechai Antokolski, sculpterer

-Yehuda Bihak, researcher

-Yaakov Bilikov, public servant

-Yehuda Leib, son of Yaakov Davidovich, doctor and writer

-Jacob, son of Jacob, bibliographer

-Louie Miller, newspaper writer

-Shlomo Bastompski, writer and educator

-Vladimir Baskin, music critic

-Abraham Aaron Broda, writer

-Abraham Broides, poet

-Yitzhak Broides, Zionist political activist

-Ruven Usher Broides, writer

-Yosef Luis Baron, rabbi and professor of philosophy

-Joshua Zev Bertonov, actor

-Aaron Mikhail Borohov, teacher and writer

-Bernard Bernsohn, art critic,( father of Marca Bernsohn)

-Sinaiv Leopold Bernstein, painter

-Ben Zion Yehudah Berkowtiz, writer

-Alexander Berkman, anarchist, partner of Emma Goldman

-Leopold Godovski, pianist and composer

-Shmuel Gorzenski, Bund activist

-Israel Isaac Goldblum, bibliographer

-Ezra Golding, author

-Aaron Gordon, doctor

-Aaron David Gordon, doctor

-Yehuda Leib Gordon, poet

-Yekutiel Gordon, doctor

-Mikhail Gordon, poet and writer

-Aaron Goland, author

-Ilya Ginsburg, sculpturer

-Gabriel Yaakov Ginsburg, financier and donor

-Yaakov Halperin, lawyer

-Chaim Grada, poet

-Avner Griliks, artist

-Avraham Grilisks, artist

-Zvi Henry Gershoni, rabbi and author

-Wolf Dormeshkin, musician

-Israel Dushman, poet and educator

-Shmuel Dykes, researcher

-Isaac Meir Dik, father of secular Yiddish literature

-Shmuel Dikstein, member of the US congress

-Eliezer Lipman Horowtiz, literature researcher

-Genja Horowitz, revolutionary

-Yitzhak Horowitz, author

-Pinkas Eliyahu Horowitz, mystic

-Shlomo Zalmand Horowtiz, author

-Markus Heyman, member of the Canadian parlament

-Chaim Yaakov Helfen, founder of the Bund

-Dvorah Ester Halper, donor and public servant

-Mikhail Halperin, one of the first pioneers in the land of Israel

-Yosef Berger, doctor and researcher of the bible

-Michael Hazkel, financier

-Yosef Wolf, cardiologist

-Yitzhak Witenberg, the leader of the partisan movement during WWII.

-Yosef Vinogrod, singer

-Rahmil Aaron Weinstein, founder of Bund

-Teibe Vinseski, resistance fighter

-Avraham Wirshovski, doctor and author

-Max Waskind, director

-Zvi Valblowski, judge

-Batjah Vernick, writer

-Paritz Vernick, writer

-Hillel Leon Zolotkov, editor

-Aaron Zundelevic, revolutionary

-Rosilia Sara Zeidfeld, mother of Max Nordoi

-Moshe Zilberstein, singer

-Shlomo Zalmand Zelkind, poet and educator

-Arnold Zelkindson, doctor and mathematician

-Yitzhak Eduard Zelkinson, first to translate Shakespeare to Hebrew

-Daniel Havelson, researcher of eastern culture

-Yitzhak Barhonas, lexicographer

-Yasha Heifetz, violinist

-Max Heifetz, biologist

-Moshe Leib Haskes Odenzig, poet and satirist

-Chaim Tebris, merchant and writer

-Kalman Tauber, rabbi and educator

-Yosef Eliyahu Treves, author and educator

-Yishayau Yonah Tcharna, pedagogist and author

-Leon Yagihez Grazovski, (Tishko), revolutionary

-Vladimir Joshelsohn, revolutionary and ethnologist

-Aaron Johnathanson, educator and poet

-Zvi Johnathanson, author and donor

-Benjamin Zajef Jacobson, lawyer and representative in the Duma

-Shlomo Jafe, member of “Bilu”, the first pioneers to Israel

-Chaim Yafim Yasharun, political activist

-Yehuda Leib Cohen, folklorist

-Avraham Dov Levinson, poet and linguist

-Michal Yosef Levisonson, poet

-Imanuel Levi, judge

-Israel Levintal, rabbi and Zionist activist

-Liuba Levison Eysenstadt, revolutionary

-Yaakov Leibowitz, physician

-Yot Lipman Litkin, mathematician and physicist

-Leon Laskov, pharmacologist

-Lisa Magon, resistance fighter

-David Magid, historian

-Hillel Noah Magid, biographer and writer

-Yosef Osif Minor, revolutionary

-Shlomo Zalkind Minor, rabbi and writer

-Chanan Yaakov Minikes, writer and publisher

-David Moshe Mitzkohn, poet

-David Mekler, publisher and editor

-Chaim Zeef Mageliot, rabbi and author

-Chaim Leib Markon, researcher

-Mordechai Nemser, rabbi

-Jonah Bernard Nathanson, physcist

-Mordechai Nathanson, author

-Taubes Segal, midwife

-Leser Segal, painter and illustrator

-Eliyahu Lewis Solomon, rabbi

-Yosef Selkind, author

-Shaul Sapir, journalist

-Asriel, son of Moshe Mashil, linguist

-Abraham Efron, writer

-Eliyahu Efron, publicist

-Yehuda Leib Polikanski, industrialist

-Aaron Eliyahu Pompianski, author

-Gershon Pludermecher, pedagogist

-Eliyahu Pinhas, researcher

-Yosef Paslas, learned man

-Shmuel Paskind, leader of the laborers

-Jahoshua Freedman, author and educator

-Yosef Peres, musician

-Elyakim Zosner, famous national poet

-Israel Schlomo Zipkin, educator

-Sara Kodes, author and midwife

-Avraham Uri Kovner, literary critic

-Mikchail Kovner, resistance fighter

-Shaul Savlikovner, historian of medicine

-Herz Koverski, phycisian and public activist

-Zemah Koppelson, revolutionary

-Avraham Kupernik, businessman and donor

-Yehudah, Julian Klatchko, author (converter to Catholicism)

-Zvi Kirsch Klatchko, head of Vilna community

-Yehudah Leib Kantor, editor and journalist

-Alter Kazisno, poet and dramatologist

-Euriah Katzenelbogen, author

-Abrah Katzenelbogen, author

-Chaim Lev Katzenelbogen, educator

-Zvi Hirsch Katzenelbogen, head of Vilna community

-David Ratner, translator

-Mikhael Rubinstein, physician

-Yeshaihu Rozovski, public activist

-Yehudah Lev Rosenthal, donor

-Moshe Rosensohn, donor and author

-Yosef Romschinski, musician

-Avraham Yaakov Rongi, gynecologist

-Moshe Richerson, linguistic

-Zv Riherson, writer

-Shmuel Reser, author

-Moshe Refes, head of Yabsketzya

-Zemah Sheved, doctor and public activist

-Joshua Steinberg, linguistics

-Maximillian Steinberg, composer and conductor

-Matityahu Straszun, one of the most learned men of Lithuania

-Shmuel Straszun, librarian

-Moshe Shelit, author and businessman

-Shmuel Hakatan, writer

-Shmuel William Shapiro, doctor

-Eliyahu Israel Shershevski, author

picture

18. Yung-Vilne standing, left to right : Shmerke Katsherginsky, Avrom

Sutzkever, Elkhonen Vogler, Khayim Grade, Leyzer Volf; siting: Moyshe Levin,

Sheyne Efron, Shimshn Kahan, Rokhl Sutzkever, Bentsye Mikhtom

picture 19. Members of the HeChaluts movement's pioneering training commune (kibbutz hachshara) in Vilnius

picture 20. make the picture black and white

Vilna’ war refugees; 1939 – 1940

Picture 21. Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzenski (1863-1940), with Rabbi Finkel in the woods near Vilna c 1940

The city of Vilna and its environs was taken by the Red Army on September 19, 1939, and on October 10 the Soviet government transferred that area to the independent republic of Lithuania. Shortly thereafter, approximately fourteen thousand Polish Jews fled to Vilna in the hope of escaping from Nazi or Soviet rule. They included such noted leaders as Menachem Begin, Moshe Sneh, and Zorah Warhaftig; approximately two thousand members of the Zionist pioneer movements (halutsim); and the rabbis and yeshiva students of more than twenty Polish yeshivas, including those of Mir, Kletsk, Radin, Kamenets - Podolski, and Baranovichi.In June 1940, the Soviets occupied Lithuania, and many of the refugees sought to emigrate at all costs. That summer, a rescue route for the Polish refugees in Lithuania opened up via East Asia, in addition to the emigration route to Palestine. Two Dutch yeshiva students obtained visas to Curacao, a Dutch colony in the Caribbean, from Jan Zwartendijk, the Dutch consul in Kovno (Kaunas), who subsequently agreed to grant such documents to other refugees. The refugees then asked the local Japanese consul, Sempo Sugihara, for the transit visas that would enable them to travel via Japan. Sugihara, on his own initiative, and later despite express instructions to the contrary, issued thousands of transit visas during the final weeks before the Soviets forced him and other consuls to leave. The refugees, headed by Dr. Zorah Warhaftig, who was in charge of the local Palestine Office for Polish Refugees, then applied for Soviet exit permits and transit visas. After extensive efforts by refugee leaders the Soviet authorities granted the refugees permission to leave, and the first group arrived in Japan in October 1940.

Transfer to

Shanghai

Once it became known that exit permits were available, efforts were made to obtain the necessary documentation by many who had previously refrained from doing so. Thus, visas to Curacao were obtained from A. M. de Jong, the Dutch consul in Stockholm, and Nicolaas Aire Johannes de Voogd, the Dutch consul in Kobe, Japan. Japanese transit visas were procured from consuls in various Russian cities, primarily with the help of the Japanese N.Y.K. (Nippon Yusen Kaisya) shipping line, which provided visas to those for whom boat tickets had been purchased. Several hundred refugees who possessed visas to the United States, Palestine, and other countries traveled via Japan, leaving the Soviet Union by means of the Curacao and/or Japanese visas; among them were such prominent rabbis as Aron Kotler, Reuven Grazowsky, and Moshe Shatzkes.

Beginning in the early spring of 1941, the Japanese attempted to halt the entry of Jewish refugees to Japan, but despite their efforts, more than 500 Jews entered between April and August. That summer, the Japanese sent those Jewish refugees who were unable to emigrate to Shanghai, where most remained for the duration of the war. During the period from October 1940 to August 1941, a total of 3,489 Jewish refugees entered Japan. Of these, 2,178 were of Polish origin, among them more than 500 rabbis and yeshiva students. In the spring of 1941, efforts were made to arrange for the entry of refugees from the Soviet Union directly to Shanghai, and the necessary permits were obtained. It is not known how many of these documents were actually utilized (apparently between 50 and 150). Courtesy of:

"Encyclopedia of the Holocaust"

©1990 Macmillan Publishing Company

New York, NY 10022

picture 22.

Art by Lionel S. Reiss. In A World At Twilight: A Portrait of the Jewish

Communities of Eastern Europe Before the Holocaust. (New York: Macmillian,

1971)

23. Return to

Vilna by Samuel Bak

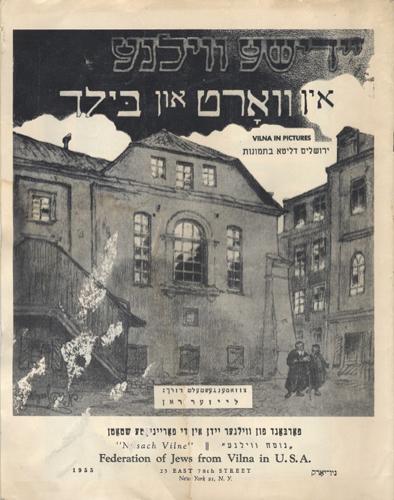

picture 24. Pictures of Vilna by the Federation of Jews from Vilna in the U.S.A ( published in 1955)

picture 25. Photo of the

great Yiddish theater company, the Vilner Trupe

Judaica Collection, Sterling Memorial Library

Yale University Library

picture 26.

picture 27. Sima nee Gurevitz with her first cousin ( nee Spektor)

And the cousins husband.

picture 28.

Slownik Geograficzny Entry

Wilno (now Vilnius, Lithuania)

Source: Slownik Geograficzny Krlestwa Polskiego - Warsaw [1893, vol. 13, pp.492-496]

Geography